Sue Bohlin provides distinctly biblical answers to your questions about homosexuality. As a Christian, it is important to understand what the Bible says and to be able to communicate this message of compassion.

Q. Some people say homosexuality is natural and moral; others say it is unnatural and immoral. How do we know?

A. Our standard can only be what God says. In Romans 1 we read,

God gave them over to shameful lusts. Even their women exchanged natural relations for unnatural ones. In the same way the men also abandoned natural relations with women and were inflamed with lust for one another. Men committed indecent acts with other men, and received in themselves the due penalty for their perversion (Romans 1:26-27).

So even though homosexual desires feel natural, they are actually unnatural, because God says they are. He also calls all sexual involvement outside of marriage immoral. (There are 44 references to fornication—sexual immorality—in the Bible.) Therefore, any form of homosexual activity, whether a one-night stand or a long-term monogamous relationship, is by definition immoral—just as any abuse of heterosexuality outside of marriage is immoral.

Q. Is homosexuality an orientation God intended for some people, or is it a perversion of normal sexuality?

A. If God had intended homosexuality to be a viable sexual alternative for some people, He would not have condemned it as an abomination. It is never mentioned in Scripture in anything but negative terms, and nowhere does the Bible even hint at approving or giving instruction for homosexual relationships. Some theologians have argued that David and Jonathan’s relationship was a homosexual one, but this claim has no basis in Scripture. David and Jonathan’s deep friendship was not sexual; it was one of godly emotional intimacy that truly glorified the Lord.

Homosexuality is a manifestation of the sin nature that all people share. At the fall of man (Genesis 3), God’s perfect creation was spoiled, and the taint of sin affected us physically, emotionally, intellectually, spiritually—and sexually. Homosexuality is a perversion of heterosexuality, which is God’s plan for His creation. The Lord Jesus said,

In the beginning the Creator made them male and female. For this reason, a man will leave his father and mother and be united to his wife, and the two will become one flesh (Matthew 19:4, 5).

Homosexual activity and pre-marital or extra-marital heterosexual activity are all sinful attempts to find sexual and emotional expression in ways God never intended. God’s desire for the person caught in the trap of homosexuality is the same as for every other person caught in the trap of the sin nature; that we submit every area of our lives to Him and be transformed from the inside out by the renewing of our minds and the purifying of our hearts.

Q. What causes a homosexual orientation?

A. This is a complex issue, and it is unfair to give simplistic answers or explanations. (However, for insight on this issue please consider our articles Answers to Questions Most Asked by Gay-Identifying Youth and “Why Doesn’t God Answer Prayers to Take Away Gay Feelings?”) Some people start out as heterosexuals, but they rebel against God with such passionate self-indulgence that they end up embracing the gay lifestyle as another form of sexual expression. As one entertainer put it, “I’m not going to go through life with one arm tied behind my back!”

But the majority of those who experience same-sex attraction sense they are “different” or “other than” from very early in life, and at some point they are encouraged to identify this difference as being gay. These people may experience “pre-conditions” that dispose them toward homosexuality, such as a sensitive and gentle temperament in boys, which is not recognized as acceptably masculine in our culture. Another may be poor eye-hand coordination that prevents a boy from doing well at sports, which is a sure way to invite shame and taunting from other boys (and, most unfortunately, from some of their own fathers and family members). Family relationships are usually very important in the development of homosexuality; the vast majority of those who struggle with same-sex attraction experienced a hurtful relationship with the same-sex parent in childhood. The presence of abuse is a recurring theme in the early lives of many homosexual strugglers. In one study, 91% of lesbian women reported childhood and adolescent abuse, 2/3 of them victims of sexual abuse.{1} There is a huge difference, however, between predispositions that affects gender identity, and the choices we make in how we handle a predisposition. Because we are made in the image of God, we can choose how we respond to the various factors that may contribute to a homosexual orientation.

Q. Wouldn’t the presence of pre-conditions let homosexuals “off the hook,” so to speak?

A. Preconditions make it easier to sin in a particular area. They do not excuse the sin. We can draw a parallel with alcoholism. Alcoholics often experience a genetic or environmental pre-condition, which makes it easier for them to fall into the sin of drunkenness. Is it a sin to want a drink? No. It’s a sin to drink to excess.

All of us experience various predispositions that make it easier for us to fall into certain sins. For example, highly intelligent people find it easier to fall into the sin of intellectual pride. People who were physically abused as children may fall into the sins of rage and violence more easily than others.

Current popular thinking says that our behavior is determined by our environment or our genes, or both. But the Bible gives us the dignity and responsibility missing from that mechanistic view of life. God has invested us with free will—the ability to make real, significant choices. We can choose our responses to the influences on our lives, or we can choose to let them control us.

Someone with a predisposition for homosexuality may fall into the sin of the homosexual behavior much more easily than a person without it. But each of us alone is responsible for giving ourselves permission to cross over from temptation into sin.

Q. What’s the difference between homosexual temptation and sin?

A. Unasked-for, uncultivated sexual desires for a person of the same sex constitute temptation, not sin. Since the Lord Jesus was “tempted in every way, just as we are (Hebrews 4:15),” He fully knows the intensity and nature of the temptations we face. But He never gave in to them.

The line between sexual temptation and sexual sin is the same for both heterosexuals and homosexuals. It is the point at which our conscious will gets involved. Sin begins with the internal acts of lusting and creating sexual fantasies. Lust is indulging one’s sexual desires by deliberately choosing to feed sexual attraction—you might say it is the sinful opposite of meditation. Sexual fantasies are conscious acts of the imagination. It is creating mental pornographic home movies. Just as the Lord said in the Sermon on the Mount, all sexual sin starts in the mind long before it gets to the point of physical expression.

Many homosexuals claim, “I never asked for these feelings. I did not choose them,” and this may be true. That is why it is significant to note that the Bible specifically condemns homosexual practices, but not undeveloped homosexual feelings (temptation). There is a difference between having sexual feelings and letting them grow into lust. When Martin Luther was talking about impure thoughts, he said, “You can’t stop the birds from flying over your head, but you can keep them from building a nest in your hair.”

Q. Isn’t it true that “Once gay, always gay?”

A. It is certainly true that most homosexuals never become heterosexual—some because they don’t want to, but most others because their efforts to change were unsuccessful. It takes spiritual submission and much emotional work to repent of sexual sin and achieve a healthy self-concept that glorifies God.

But for the person caught in the trap of homosexual desires who wants sexual and emotional wholeness, there is hope in Christ. In addressing the church at Corinth, the Apostle Paul lists an assortment of deep sins, including homosexual offenses. He says,

And that is what some of you were. But you were washed, you were sanctified, you were justified in the name of the Lord Jesus Christ (1 Corinthians 6:11).

This means there were former homosexuals in the church at Corinth! The Lord’s loving redemption includes eventual freedom for all sin that is yielded to Him. Some (rare) people experience no homosexual temptations ever again. But for most others who are able to achieve change, homosexual desires are gradually reduced from a major problem to a minor nuisance that no longer dominates their lives. The probability of heterosexual desires returning or emerging depends on a person’s sexual history.

But the potential for heterosexuality is present in everyone because God put it there.

See our article “Can Homosexuals Change?” at www.probe.org/can-homosexuals-change/.

Q. If homosexuality is such an abomination to God, why doesn’t it disappear when someone becomes a Christian?

A. When we are born again, we bring with us all of our emotional needs and all of our old ways of relating. Homosexuality is a relational problem of meeting emotional needs the wrong way; it is not an isolated problem of mere sexual preference. With the power of the indwelling Spirit, a Christian can cooperate with God to change this unacceptable part of life. Some people—a very few—are miraculously delivered from homosexual struggles. But for the majority, real change is slow. As in dealing with any besetting sin, it is a process, not an event. Sin’s power over us is broken at the moment we are born again, but learning to depend on the Holy Spirit to say no to sin and yes to godliness takes time. 2 Corinthians 3:18 says, “We…are being transformed into His likeness from glory to glory.” Transformation (this side of eternity!) is a process that takes a while. Life in a fallen world is a painful struggle. It is not a pleasant thing to have two oppositional natures at war within us!

Homosexuality is not one problem; it is symptomatic of other, deeper problems involving emotional needs and an unhealthy self-concept. Salvation is only the beginning of emotional health. It allows us to experience human intimacy as God intended us to, finding healing for our damaged emotions. It isn’t that faith in Christ isn’t enough; faith in Christ is the beginning.

Q. Does the fact that I had an early homosexual experience mean I’m gay?

A. Sex is strictly meant for adults. The Song of Solomon says three times, “Do not arouse or awaken love until it so desires.” This is a warning not to raise sexual feelings until the time is right. Early sexual experience can be painful or pleasurable, but either way, it constitutes child abuse. It traumatizes a child or teen. This loss of innocence does need to be addressed and perhaps even grieved through, but doesn’t mean you’re gay.

Sexual experimentation is something many children and teens do as a part of growing up. You may have enjoyed the feelings you experienced, but that is because God created our bodies to respond to pleasure. It probably made you feel confused and ashamed, which is an appropriate response to an inappropriate behavior. Don’t let anyone tell you it means you’re gay: it means you’re human.

Even apart from the sexual aspect, though, our culture has come to view close friendships with a certain amount of suspicion. If you enjoy emotional intimacy with a friend of the same sex, especially if it is accompanied by the presence of sexual feelings that emerge in adolescence, you can find yourself very confused. But it doesn’t mean you’re gay.

It is a tragic myth that once a person has a homosexual experience, or even thinks about one, that he or she is gay for life.

Q. Are homosexuals condemned to hell?

A. Homosexuality is not a “heaven or hell” issue. The only determining factor is whether a person has been reconciled to God through Jesus Christ.

In 1 Corinthians 6, Paul says that homosexual offenders and a whole list of other sinners will not inherit the kingdom of God. But then he reminds the Corinthians that they have been washed, sanctified, and justified in Jesus’ name. Paul makes a distinction between unchristian behavior and Christian behavior. He’s saying, “You’re not pagans anymore, you are a holy people belonging to King Jesus. Now act like it!”

If homosexuality doesn’t send anyone to hell, then can the believer indulge in homosexual behavior, safe in his or her eternal security? As Paul said, “May it never be!” If someone is truly a child of God, he or she cannot continue sinful behavior that offends and grieves the Father without suffering the consequences. God disciplines those He loves (Hebrews 12:6). This means that ultimately, no believer gets away with continued, unrepented sin. The discipline may not come immediately, but it will come.

Q. How do I respond when someone in my life tells me he or she is gay?

A. Take your cue from the Lord Jesus. He didn’t avoid sinners; He ministered grace and compassion to them—without ever compromising His commitment to holiness. Start by cultivating a humble heart, especially concerning the temptation to react with judgmental condescension. As Billy Graham said, “Never take credit for not falling into a temptation that never tempted you in the first place.”

Seek to understand your gay friends’ feelings. Are they comfortable with their gayness, or bewildered and resentful of it? Understanding people doesn’t mean that you have to agree with them—but it is the best way to minister grace and love in a difficult time. Accept the fact that, to this person, these feelings are normal. You can’t change their minds or their feelings. Too often, parents will send their gay child to a counselor and say, “Fix him.” It just doesn’t work that way.

As a Christian, you are a light shining in a dark place. Be a friend with a tender heart and a winsome spirit; the biggest problem of homosexuals is not their sexuality, but their need for Jesus Christ. At the same time, pre-decide what your boundaries will be about what behavior you just cannot condone in your presence. One college student I know excuses herself from a group when the affection becomes physical; she just gets up and leaves. It is all right to be uncomfortable around blatant sin; you do not have to subject yourself—and the Holy Spirit within you—to what grieves Him. Consider how you would be a friend to people who are living promiscuous heterosexual lives. Like the Lord, we need to value and esteem the person without condoning the sin.

Note

1. Anne Paulk, Restoring Sexual Identity (Eugene OR: Harvest House, 2003), p. 246.

For further reading:

• Bergner, Mario. Setting Love in Order: Hope and Healing for the Homosexual. Baker, 1995.

• Paulk, Anne. Restoring Sexual Identity. Eugene OR: Harvest House, 2003.

• Dallas, Joe. Desires in Conflict. Eugene, OR: Harvest House, 1991. (Particularly good!)

• Konrad, Jeff. You Don’t Have to Be Gay. Pacific Publishing, 1987. (This is directed at young men. I can’t recommend this one highly enough.)

• Satinover, Jeffrey. Homosexuality and the Politics of Truth. Baker, 1996.

• Schmidt, Thomas E. Straight & Narrow? : Compassion & Clarity in the Homosexuality Debate. Intervarsity Press, 1995.

• Worthen, Anita and Bob Davies. Someone I Love is Gay: How Family and Friends Can Respond. Intervarsity Press, 1996.

• The website of Living Hope Ministries, an outreach in the Dallas/Ft. Worth area. Of particular interest are the online testimonies and especially an excellent online support group, a confidential, free, moderated message board for strugglers, overcomers and those who seek to encourage and uplift. www.livehope.org

© 2003 Probe Ministries International

True scientific revolutions that impact more than a single discipline rarely occur more than once a century. Newton’s Principia, published in the 17th century, truly qualifies. Darwin’s Origin of Species, published in 1859, also belongs on the list. Standing in the wings, ready to join these esteemed works and perhaps even overturn the latter, stands William Dembski’s The Design Inference.

True scientific revolutions that impact more than a single discipline rarely occur more than once a century. Newton’s Principia, published in the 17th century, truly qualifies. Darwin’s Origin of Species, published in 1859, also belongs on the list. Standing in the wings, ready to join these esteemed works and perhaps even overturn the latter, stands William Dembski’s The Design Inference. William Dembski’s groundbreaking book, The Design Inference from Cambridge University Press, is highly technical. Dembski has therefore written a follow-up book titled, Intelligent Design: The Bridge between Science and Theology,

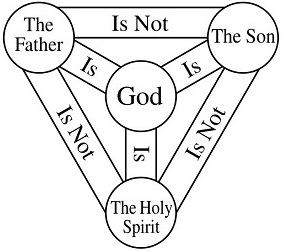

William Dembski’s groundbreaking book, The Design Inference from Cambridge University Press, is highly technical. Dembski has therefore written a follow-up book titled, Intelligent Design: The Bridge between Science and Theology, Even though it’s short, this definition is both a mouthful and a mind full. But let’s settle on four basic concepts before we move on to the implications. At the heart of the definition of the Blessed Trinity we have: one God, three Persons, who are coequal and coeternal. With this sketch in place, then, we are ready to move out and survey the importance of the Trinity with respect to the Christian worldview and its practical aspects for the Christian life. At the end of our discussion I truly hope that we can affirm together our love for the Trinity.

Even though it’s short, this definition is both a mouthful and a mind full. But let’s settle on four basic concepts before we move on to the implications. At the heart of the definition of the Blessed Trinity we have: one God, three Persons, who are coequal and coeternal. With this sketch in place, then, we are ready to move out and survey the importance of the Trinity with respect to the Christian worldview and its practical aspects for the Christian life. At the end of our discussion I truly hope that we can affirm together our love for the Trinity.