The Bailout

Anyone watching the news or looking at their checking account knows that we are in for some tough economic times. I want to spend some time looking at how we arrived at this place and set forth some biblical principles that we collectively and individually need to follow.

Who would have imagined a year ago we would be talking about spending such enormous amounts of money on a bailout? The first bailout was for $700 billion. When these numbers are so big, we lose all proportion of their size and potential impact. So let me use a few comparisons from a recent Time magazine article to make my point.{1}

If we took $700 billion and gave it to every person in America, they would receive a check for $2,300. Or if we decided to give that money instead to every household in America, they would receive $6,200.

What if we were able to use $700 billion to fund the government for a year? If we did so, it would fully fund the Defense Department, the State Department, the Treasury, the Department of Education, Veterans Affairs, the Department of the Interior, and NASA. If instead we decided to pay off some of the national debt, it would retire seven percent of that debt.

Are you a sports fan? What if we used that money to buy sports teams? This is enough money to buy every NFL team, every NBA team, and every Major League Baseball team. But we would have so much left over that we could also buy every one of these teams a new stadium. And we would still have so much money left over that we could pay each of these players $191 million for a year.

Of course this is just the down payment. When we add up all the money for bailouts and the economic stimulus, the numbers are much larger (some estimate on the order of $4.6 trillion).

Jim Bianco (of Bianco Research) crunched the inflation adjusted numbers.{2} The current bailout actually costs more than all of the following big budget government expenditures: the Marshall Plan ($115.3 billion), the Louisiana Purchase ($217 billion), the New Deal ($500 billion [est.]), the Race to the Moon ($237 billion), the Savings and Loan bailout ($256 billion), the Korean War ($454 billion), the Iraq war ($597 billion), the Vietnam War ($698 billion), and NASA ($851.2 billion).

Even if you add all of this up, it actually comes to $3.9 trillion and so is still $700 billion short (which incidentally is the original cost of one of the bailout packages most people have been talking about).

Keep in mind that these are inflation-adjusted figures. So you can begin to see that what has happened this year is absolutely unprecedented. Until you run the numbers, it seems like Monopoly money. But the reality is that it is real money that must either be borrowed or printed. There is no stash of this amount of money somewhere that Congress is putting into the economy.

What Caused the Financial Crisis?

What caused the financial crisis? Answering that question in a few minutes may be difficult, but let me give it a try.

First, there was risky mortgage lending. Some of that was due to government influence through the Community Reinvestment Act which encouraged commercial banks and savings associations to loan money to people in low-income and moderate-income neighborhoods. And part of it was due to the fact that some mortgage lenders were aggressively pushing subprime loans. Some did this by fraudulently overestimating the value of the homes or by overstating the lender’s income. When these people couldn’t pay on their loan, they lost their homes (and we had a record number of foreclosures).

Next, the lenders who pushed those bad loans went bankrupt. Then a whole series of dominoes began to fall. Government sponsored enterprises like Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac as well as financial institutions like Bear Stearns, Lehman Brothers, Merrill Lynch and AIG began to fail.

As this was happening, commentators began to blame government, the financial institutions, Wall Street, and even those who obtained mortgages. Throughout the presidential campaign and into 2009 there was a cry that this was the result of shredded consumer protections and deregulation.

So is the current crisis a result of these policies? Is deregulation the culprit? Kevin Hassett has proposed a simple test of this view.{3} He points out that countries around the world have very different regulatory structures. Some have relatively light regulatory structures, while others have much more significant intrusion into markets.

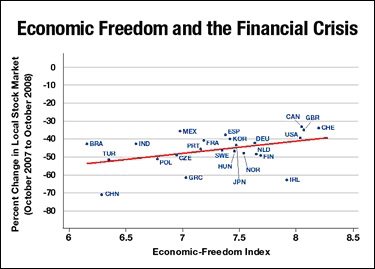

If deregulation is the problem, then those countries that have looser regulations should have a greater economic crisis. But that is not what we find. If you plot the degree of economic freedom of a country on the x-axis and the percent of change in the local stock market on the y-axis, you find just the opposite of that prediction.

If the crisis were a result of deregulation, then the line should be downward sloping (meaning that countries that are freer economically had a biggest collapse in their stock markets). But the line slopes up. That seems to imply that countries that are economically free have suffered less than countries that are not. While it may be true that a single graph and a statistical correlation certainly does not tell the whole story, it does suggest that the crisis was not due to deregulation.

The End of Prosperity

It is interesting that as the financial crisis was unfolding, a significant economic book was coming on the market. The title of the book is The End of Prosperity.{4}

Recently I interviewed Stephen Moore with the Wall Street Journal. He is the co-author with Arthur Laffer and Peter Tanous of The End of Prosperity. The book provides excellent documentation to many of the economic issues that I have discussed in the past but also looks ahead to the future.

The authors show that, contrary to conventional wisdom, the middle class has been doing better in America. They show how people in high tax states are moving to low tax states. And they document the remarkable changes in Ireland due to lowering taxes. I have talked about some of these issues in previous articles and in my radio commentaries. Their book provides ample endnotes and documentation to buttress these conclusions.

What is most interesting about the book is that it was written before the financial meltdown of the last few months. Those of us who write books have to guess what circumstances will be when the book is finally published. These authors probably had less of a lag time, but I doubt any of them anticipated the economic circumstances that we currently find.

Arthur Laffer, in a column in the Wall Street Journal, believes that “financial panics, if left alone, rarely cause much damage to the real economy.”{5} But he then points out that government could not leave this financial meltdown alone. He laments that taxpayers have to pay for these bailouts because homeowners and lenders lost money. He notes: “If the house’s value had appreciated, believe you me the overleveraged homeowners and the overly aggressive banks would never have shared their gain with the taxpayers.”

He is also concerned with the ability of government to deal with the problem. He says, “Just watch how Congress and Barney Frank run the banks. If you thought they did a bad job running the post office, Amtrak, Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac and the military, just wait till you see what they’ll do with Wall Street.”

The reason the authors wrote The End of Prosperity was to set forth what has worked in the past as a prescription for the future. They were concerned that tax rates were headed up and not down, that the dollar is falling, and that America was turning it back on trade and globalization. They also were concerned that the federal budget was spiraling out of control and that various campaign promises (health care, energy policy, environmental policy) would actually do more harm than good.

One of their final chapters is titled “The Death of Economic Sanity.” They feared that the current push toward more governmental intervention would kill the economy. While they hoped that politicians would go slow instead of launching an arsenal of economy killers, they weren’t too optimistic. That is why they called their book The End of Prosperity.

The Future of Affluence

Let’s see what another economist has to say. The Bible tells us that there is wisdom in many counselors (Proverbs 15:22). So when we see different economists essentially saying the same thing, we should pay attention.

Robert Samuelson, writing in Newsweek magazine, talks about “The Future of Affluence.”{6} He begins by talking about the major economic dislocations of the last few months:

“Government has taken over mortgage giants Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. The Treasury has made investments in many of the nation’s major banks. The Federal Reserve is pumping out $1 trillion to stabilize credit markets. U.S. unemployment is at 6.1 percent, up from a recent low of 4.4 percent, and headed toward 8 percent, by some estimates.”

Samuelson says that a recovery will take place but we may find it unsatisfying. He believes we will lapse into a state of “affluent deprivation.” By that he doesn’t mean poverty, but he does mean that there will be a state of mind in which people will feel poorer than they feel right now.

He says that the U.S. economy has benefited for roughly a quarter century “from the expansionary side effects of falling inflation—lower interest rates, greater debt, higher personal wealth—to the point now that we have now overdosed on its pleasures and are suffering a hangover.” Essentially, prosperity bred habits, and many of these habits were bad habits. Personal savings went down, and debt and spending went up.

Essentially we are suffering from “affluenza.” Actually that is the title of a book published many years ago to define the problem of materialism in general and consumerism in particular.

The authors say that the virus of affluenza “is not confined to the upper classes but has found it ways throughout our society. Its symptoms affect the poor as well as the rich . . . affluenza infects all of us, though in different ways.”{7} The authors go on to say that “the affluenza epidemic is rooted in the obsessive, almost religious quest for economic expansion that has become the core principle of what is called the American dream.”

Anyone looking at some of the social statistics for the U.S. might conclude that our priorities are out of whack. We spend more on shoes, jewelry, and watches than on higher education. We spend much more on auto maintenance than on religious and welfare activities. We have twice as many shopping centers as high schools.

The cure for the virus affluenza is a proper biblical perspective toward life. Jesus tells the parable of a rich man who decides to tear down his barns and build bigger ones (Luke 12:18). He is not satisfied with his current situation, but is striving to make it better. Today most of us have adjusted to a life of affluence as normal and need to actively resist the virus of affluenza.

Squanderville

Warren Buffett tells the story of two side-by-side islands of equal size: Thriftville and Squanderville.{8} On these islands, land is a capital asset. At first, the people on both islands are at a subsistence level and work eight hours a day to meet their needs. But the Thrifts realize that if they work harder and longer, they can produce a surplus of goods they can trade with the Squanders. So the Thrifts decide to do some serious saving and investing and begin to work sixteen hours a day. They begin exporting to Squanderville.

The people of Squanderville like the idea of working less. They can begin to live their lives free from toil. So they willingly trade for these goods with “Squanderbonds” that are denominated in “Squanderbucks.”

Over time, the citizens of Thriftville accumulate lots of Squanderbonds. Some of the pundits in Squanderville see trouble. They foresee that the Squanders will now have to put in double time to eat and pay off their debt.

At about the same time, the citizens of Thriftville begin to get nervous and wonder if the Squanders will make good on their Squanderbonds (which are essentially IOUs). So the Thrifts start selling their Squanderbonds for Squanderbucks. Then they use the Squanderbucks to buy Squanderville land. Eventually the Thrifts own all of Squanderville.

Now the citizens of Squanderville must pay rent to live on the land which is owned by the Thrifts. The Squanders feel like they have been colonized by purchase rather than conquest. And they also face a horrible set of circumstances. They now must not only work eight hours in order to eat, but they must work additional hours to service the debt and pay Thriftville rent on the land they sold to them.

Does this story sound familiar? It should. Squanderville is America.

Economist Peter Schiff says that the United States has “been getting a free ride on the global gravy train.” He sees other countries starting to reclaim their resources and manufactured goods. As a result, Americans are getting priced out of the market because these other countries are going to enjoy the consumption of goods that Americans previously purchased.

He says: “If America had maintained a viable economy and continued to produce goods instead of merely consuming them, and if we had saved money instead of borrowing, our standard of living could rise with everybody else’s. Instead, we gutted our manufacturing, let our infrastructure decay, and encouraged our citizens to borrow with reckless abandon.”{9}

It appears we have been infected with the virus of affluenza. The root problem is materialism that often breeds discontent. We want more of the world and its possessions rather than more of God and His will in our lives. What a contrast to what Paul says in Philippians where he counts all things to be loss (3:7-8) and instead has learned to be content (4:11). He goes on to talk about godliness with contentment in 1 Timothy 6:6-7. Contentment is an effective antidote to materialism and the foundation to a proper biblical perspective during these tough economic times.

Notes

1. “What Else You Could Spend $700 Billion On,” Time, September 2008, www.eandppub.com/2008/09/what-else-you-c.html.

2. Barry Ritholtz, “Big Bailouts, Bigger Bucks,” Bailouts, Markets, Taxes and Policy, www.ritholtz.com/blog/2008/11/big-bailouts-bigger-bucks/.

3. Kevin Hassett, “The Regulators’ Rough Ride,” National Review, 15 December 2008, 10.

4. Arthur Laffer, Stephen Moore, and Peter Tanous, The End of Prosperity (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2008).

5. Arthur Laffer, “The Age of Prosperity Is Over,” Wall Street Journal, 27 October, 2008, A19, online.wsj.com/article/SB122506830024970697.html.

6. Robert Samuelson, “The Future of Affluence,” Newsweek, 10 November 2008, 26-30.

7. John DeGraaf, David Wann, and Thomas Naylor, Affluenza: The All-Consuming Epidemic, 2nd ed. (SF: Berrett-Koehler, 2005), xviii.

8. Warren Buffett, “America’s Growing Trade Deficit Is Selling the Nation Out From Under Us,” Fortune, 26 October 2003.

9. Kirk Shinkle, “Permabear Peter Schiff’s Worst-Case Scenario,” U.S. News and World Report, 10 December 2008, tinyurl.com/63sqkh

© 2009 Probe Ministries