Dr. Michael Gleghorn critiques The Da Vinci Code’s theories, demonstrating that most of these theories are simply false.

This article is also available in Spanish.

This article is also available in Spanish.

Introduction to The Da Vinci Code

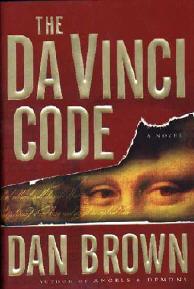

Dan Brown’s novel, The Da Vinci Code,{1} has generated a huge amount of interest from the reading public. About forty million copies have been sold worldwide.{2} And Ron Howard and Sony Pictures have brought the story to theatres.{3} To help answer some of the challenges which this novel poses to biblical Christianity, Probe has teamed up with EvanTell, an evangelism training ministry, to produce a DVD series called Redeeming The Da Vinci Code. The series aims to strengthen the faith of believers and equip them to share their faith with those who see the movie or have read the book.{4} I hope this article will also encourage you to use this event to witness to the truth to friends or family who have read the book or seen the movie.

Why so much fuss about a novel? The story begins with the murder of the Louvre’s curator. But this curator isn’t just interested in art; he’s also the Grand Master of a secret society called the Priory of Sion. The Priory guards a secret that, if revealed, would discredit biblical Christianity. Before dying, the curator attempts to pass on the secret to his granddaughter Sophie, a cryptographer, and Harvard professor Robert Langdon, by leaving a number of clues that he hopes will guide them to the truth.

So what’s the secret? The location and identity of the Holy Grail. But in Brown’s novel, the Grail is not the cup allegedly used by Christ at the Last Supper. It’s rather Mary Magdalene, the wife of Jesus, who carried on the royal bloodline of Christ by giving birth to His child! The Priory guards the secret location of Mary’s tomb and serves to protect the bloodline of Jesus that has continued to this day!

Does anyone take these ideas seriously? Yes; they do. This is partly due to the way the story is written. The first word one encounters in The Da Vinci Code, in bold uppercase letters, is the word “FACT.” Shortly thereafter Brown writes, “All descriptions of artwork, architecture, documents, and secret rituals in this novel are accurate.”{5} And the average reader, with no special knowledge in these areas, will assume the statement is true. But it’s not, and many have documented some of Brown’s inaccuracies in these areas.{6}

Brown also has a way of making the novel’s theories about Jesus and the early church seem credible. The theories are espoused by the novel’s most educated characters: a British royal historian, Leigh Teabing, and a Harvard professor, Robert Langdon. When put in the mouths of these characters, one comes away with the impression that the theories are actually true. But are they?

In this article, I’ll argue that most of what the novel says about Jesus, the Bible, and the history of the early church is simply false. I’ll also say a bit about how this material can be used in evangelism.

Did Constantine Embellish Our Four Gospels?

Were the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John, which were later to be officially recognized as part of the New Testament canon, intentionally embellished in the fourth century at the command of Emperor Constantine? This is what Leigh Teabing, the fictional historian in The Da Vinci Code, suggests. At one point he states, “Constantine commissioned and financed a new Bible, which omitted those gospels that spoke of Christ’s human traits and embellished those gospels that made Him godlike” (234). Is this true?

In a letter to the church historian Eusebius, Constantine did indeed order the preparation of “fifty copies of the sacred Scriptures.”{7} But nowhere in the letter does he command that any of the Gospels be embellished in order to make Jesus appear more godlike. And even if he had, it would have been virtually impossible to get faithful Christians to accept such accounts.

Before the reign of Constantine, the church suffered great persecution under Emperor Diocletian. It’s hard to believe that the same church that had withstood this persecution would jettison their cherished Gospels and embrace embellished accounts of Jesus’ life! It’s also virtually certain that had Constantine tried such a thing, we’d have lots of evidence for it in the writings of the church fathers. But we have none. Not one of them mentions an attempt by Constantine to alter any of our Gospels. And finally, to claim that the leaders of the fourth century church, many of whom had suffered persecution for their faith in Christ, would agree to join Constantine in a conspiracy of this kind is completely unrealistic.

One last point. We have copies of the four Gospels that are significantly earlier than Constantine and the Council of Nicaea (or Nicea). Although none of the copies are complete, we do have nearly complete copies of both Luke and John in a codex dated between A.D. 175 and 225—at least a hundred years before Nicaea. Another manuscript, dating from about A.D. 200 or earlier, contains most of John’s Gospel.{8} But why is this important?

First, we can compare these pre-Nicene manuscripts with those that followed Nicaea to see if any embellishment occurred. None did. Second, the pre-Nicene versions of John’s Gospel include some of the strongest declarations of Jesus’ deity on record (e.g. 1:1-3; 8:58; 10:30-33). That is, the most explicit declarations of Jesus’ deity in any of our Gospels are already found in manuscripts that pre-date Constantine by more than a hundred years!

If you have a non-Christian friend who believes these books were embellished, you might gently refer them to this evidence. Then, encourage them to read the Gospels for themselves and find out who Jesus really is.

But what if they think these sources can’t be trusted?

Can We Trust the Gospels?

Although there’s no historical basis for the claim that Constantine embellished the New Testament Gospels to make Jesus appear more godlike, we must still ask whether the Gospels are reliable sources of information about Jesus. According to Teabing, the novel’s fictional historian, “Almost everything our fathers taught us about Christ is false” (235). Is this true? The answer largely depends on the reliability of our earliest biographies of Jesus—the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John.

Each of these Gospels was written in the first century A.D. Although they are technically anonymous, we have fairly strong evidence from second century writers such as Papias (c. A.D. 125) and Irenaeus (c. A.D. 180) for ascribing each Gospel to its traditional author. If their testimony is true (and we’ve little reason to doubt it), then Mark, the companion of Peter, wrote down the substance of Peter’s preaching. And Luke, the companion of Paul, carefully researched the biography that bears his name. Finally, Matthew and John, two of Jesus’ twelve disciples, wrote the books ascribed to them. If this is correct, then the events recorded in these Gospels “are based on either direct or indirect eyewitness testimony.”{9}

But did the Gospel writers intend to reliably record the life and ministry of Jesus? Were they even interested in history, or did their theological agendas overshadow any desire they may have had to tell us what really happened? Craig Blomberg, a New Testament scholar, observes that the prologue to Luke’s Gospel “reads very much like prefaces to other generally trusted historical and biographical works of antiquity.” He further notes that since Matthew and Mark are similar to Luke in terms of genre, “it seems reasonable that Luke’s historical intent would closely mirror theirs.”{10} Finally, John tells us that he wrote his Gospel so that people might believe that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God, and that by believing they might have life in His name (20:31). While this statement admittedly reveals a theological agenda, Blomberg points out that “if you’re going to be convinced enough to believe, the theology has to flow from accurate history.”{11}

Interestingly, the disciplines of history and archaeology are a great help in corroborating the general reliability of the Gospel writers. Where these authors mention people, places, and events that can be checked against other ancient sources, they are consistently shown to be quite reliable. We need to let our non-Christian friends know that we have good grounds for trusting the New Testament Gospels and believing what they say about Jesus.

But what if they ask about those Gospels that didn’t make it into the New Testament? Specifically, what if they ask about the Nag Hammadi documents?

The Nag Hammadi Documents

Since their discovery in 1945, there’s been much interest in the Nag Hammadi texts. What are these documents? When were they written, and by whom, and for what purpose? According to Teabing, the historian in The Da Vinci Code, the Nag Hammadi texts represent “the earliest Christian records” (245). These “unaltered gospels,” he claims, tell the real story about Jesus and early Christianity (248). The New Testament Gospels are allegedly a later, corrupted version of these events.

The only difficulty with Teabing’s theory is that it’s wrong. The Nag Hammadi documents are not “the earliest Christian records.” Every book in the New Testament is earlier. The New Testament documents were all written in the first century A.D. By contrast, the dates for the Nag Hammadi texts range from the second to the third century A.D. As Darrell Bock observes in Breaking The Da Vinci Code, “The bulk of this material is a few generations removed from the foundations of the Christian faith, a vital point to remember when assessing the contents.”{12}

What do we know about the contents of these books? It is generally agreed that the Nag Hammadi texts are Gnostic documents. The key tenet of Gnosticism is that salvation comes through secret knowledge. As a result, the Gnostic Gospels, in striking contrast to their New Testament counterparts, place almost no value on the death and resurrection of Jesus. Indeed, Gnostic Christology had a tendency to separate the human Jesus from the divine Christ, seeing them as two distinct beings. It was not the divine Christ who suffered and died; it was merely the human Jesus—or perhaps even Simon of Cyrene.{13} It didn’t matter much to the Gnostics because in their view the death of Jesus was irrelevant for attaining salvation. What was truly important was not the death of the man Jesus but the secret knowledge brought by the divine Christ. According to the Gnostics, salvation came through a correct understanding of this secret knowledge.{14}

Clearly these doctrines are incompatible with the New Testament teaching about Christ and salvation (e.g. Rom. 3:21-26; 5:1-11; 1 Cor. 15:3-11; Tit. 2:11-14). Ironically, they’re also incompatible with Teabing’s view that the Nag Hammadi texts “speak of Christ’s ministry in very human terms” (234). The Nag Hammadi texts actually present Christ as a divine being, though quite differently from the New Testament perspective.{15}

Thus, the Nag Hammadi texts are both later than the New Testament writings and characterized by a worldview that is entirely alien to their theology. We must explain to our non-Christian friends that the church fathers exercised great wisdom in rejecting these books from the New Testament.

But what if they ask us how it was decided what books to include?

The Formation of the New Testament Canon

In the early centuries of Christianity, many books were written about the teachings of Jesus and His apostles. Most of these books never made it into the New Testament. They include such titles as The Gospel of Philip, The Acts of John, and The Apocalypse of Peter. How did the early church decide what books to include in the New Testament and what to reject? When were these decisions made, and by whom? According to the Teabing, “The Bible, as we know it today, was collated by . . . Constantine the Great” (231). Is this true?

The early church had definite criteria that had to be met for a book to be included in the New Testament. As Bart Ehrman observes, a book had to be ancient, written close to the time of Jesus. It had to be written either by an apostle or a companion of an apostle. It had to be consistent with the orthodox understanding of the faith. And it had to be widely recognized and accepted by the church.{16} Books that didn’t meet these criteria weren’t included in the New Testament.

When were these decisions made? And who made them? There wasn’t an ecumenical council in the early church that officially decreed that the twenty-seven books now in our New Testament were the right ones.{17} Rather, the canon gradually took shape as the church recognized and embraced those books that were inspired by God. The earliest collections of books “to circulate among the churches in the first half of the second century” were our four Gospels and the letters of Paul.{18} Not until the heretic Marcion published his expurgated version of the New Testament in about A.D. 144 did church leaders seek to define the canon more specifically.{19}

Toward the end of the second century there was a growing consensus that the canon should include the four Gospels, Acts, the thirteen Pauline epistles, “epistles by other ‘apostolic men’ and the Revelation of John.”{20} The Muratorian Canon, which dates toward the end of the second century, recognized every New Testament book except Hebrews, James, 1 and 2 Peter, and 3 John. Similar though not identical books were recognized by Irenaeus in the late second century and Origen in the early third century. So while the earliest listing of all the books in our New Testament comes from Athanasius in A.D. 367, there was widespread agreement on most of these books (including the four Gospels) by the end of the second century. By sharing this information “with gentleness and respect” (1 Pet. 3:15), we can help our friends see that the New Testament canon did not result from a decision by Constantine.

Who Was Mary Magdalene? (Part 1)

Mary Magdalene, of course, is a major figure in The Da Vinci Code. Let’s take a look at Mary, beginning by addressing the unfortunate misconception that she was a prostitute. Where did this notion come from? And why do so many people believe it?

According to Leigh Teabing, the popular understanding of Mary Magdalene as a prostitute “is the legacy of a smear campaign . . . by the early Church.” In Teabing’s view, “The Church needed to defame Mary . . . to cover up her dangerous secret—her role as the Holy Grail” (244). Remember, in this novel the Holy Grail is not the cup used by Jesus at the Last Supper. Instead it’s Mary Magdalene, who’s alleged to have been both Jesus’ wife and the one who carried His royal bloodline in her womb.

How should we respond to this? Did the early church really seek to slander Mary as a prostitute in order to cover up her intimate relationship with Jesus? The first recorded instance of Mary Magdalene being misidentified as a prostitute occurred in a sermon by Pope Gregory the Great in A.D. 591.{21} Most likely, this wasn’t a deliberate attempt to slander Mary’s character. Rather, Gregory probably misinterpreted some passages in the Gospels, resulting in his incorrectly identifying Mary as a prostitute.

For instance, he may have identified the unnamed sinful woman in Luke 7, who anointed Jesus’ feet, with Mary of Bethany in John 12, who also anointed Jesus’ feet shortly before His death. This would have been easy to do because, although there are differences, there are also many similarities between the two separate incidents. If Gregory thought the sinful woman of Luke 7 was the Mary of John 12, he may then have mistakenly linked this woman with Mary Magdalene. Interestingly, Luke mentions Mary Magdalene for the first time at the beginning of chapter 8, right after the story of Jesus’ anointing in Luke 7. Since the unnamed woman in Luke 7 was likely guilty of some kind of sexual sin, if Gregory thought this woman was Mary Magdalene, then it wouldn’t be too great a leap to infer she was a prostitute.

If you’re discussing the novel with someone who is hostile toward the church, don’t be afraid to admit that the church has sometimes made mistakes. We can agree that Gregory was mistaken when he misidentified Mary as a prostitute. But we must also observe that it’s quite unlikely that this was part of a smear campaign by the early church. We must remind our friends that Christians make mistakes—and even sin—just like everyone else (Rom. 3:23). The difference is that we’ve recognized our need for a Savior from sin. And in this respect, we’re actually following in the footsteps of Mary Magdalene (John 20:1-18)!

Who Was Mary Magdalene? (Part 2)

What do our earliest written sources reveal about the real Mary Magdalene? According to Teabing, Mary was the wife of Jesus, the mother of His child, and the one whom He intended to establish the church after His death (244-48). In support of these theories, Teabing appeals to two of the Gnostic Gospels: The Gospel of Philip and The Gospel of Mary [Magdalene]. Let’s look first at The Gospel of Mary.

The section of this Gospel quoted in the novel presents an incredulous apostle Peter who simply can’t believe that the risen Christ has secretly revealed information to Mary that He didn’t reveal to His male disciples. Levi rebukes Peter: “If the Saviour made her worthy, who are you . . . to reject her? Surely the Saviour knows her very well. That is why he loved her more than us” (247).

What can we say about this passage? First, we must observe that nowhere in this Gospel are we told that Mary was Jesus’ wife or the mother of His child. Second, many scholars think this text should probably be read symbolically, with Peter representing early Christian orthodoxy and Mary representing a form of Gnosticism. This Gospel is probably claiming that “Mary” (that is, the Gnostics) has received divine revelation, even if “Peter” (that is, the orthodox) can’t believe it.{22} Finally, even if this text should be read literally, we have little reason to think it’s historically reliable. It was likely composed sometime in the late second century, about a hundred years after the canonical Gospels.{23} So, contrary to what’s implied in the novel, it certainly wasn’t written by Mary Magdalene—or any of Jesus’ other original followers.{24}

If we want reliable information about Mary, we must turn to our earliest sources—the New Testament Gospels. These sources tell us that Mary was a follower of Jesus from the town of Magdala. After Jesus cast seven demons out of her, she (along with other women) helped support His ministry (Luke 8:1-3). She witnessed Jesus’ death, burial, and resurrection, and was the first to see the risen Christ (Matt. 27:55-61; John 20:11-18). Jesus even entrusted her with proclaiming His resurrection to His male disciples (John 20:17-18). In this sense, Mary was an “apostle” to the apostles.{25} This is all the Gospels tell us about Mary.{26} We can agree with our non-Christian friends that she was a very important woman. But we must also remind them that there’s nothing to suggest that she was Jesus’ wife, or that He intended her to lead the church.

All this aside, someone who’s read The Da Vinci Code might still have questions about The Gospel of Philip? Doesn’t this text indicate that Mary and Jesus were married?

Was Jesus Married? (Part 1)

Undoubtedly, the strongest textual evidence that Jesus was married comes from The Gospel of Philip. So it’s not surprising that Leigh Teabing, should appeal to this text. The section of this Gospel quoted in the novel reads as follows:

And the companion of the Saviour is Mary Magdalene. Christ loved her more than all the disciples and used to kiss her often on her mouth. The rest of the disciples were offended by it and expressed disapproval. They said to him, “Why do you love her more than all of us?” (246).

Now, notice that the first line refers to Mary as the companion of the Savior. In the novel, Teabing clinches his argument that Jesus and Mary were married by stating, “As any Aramaic scholar will tell you, the word companion, in those days, literally meant spouse” (246). This sounds pretty convincing. Was Jesus married after all?

When discussing this issue with a non-Christian friend, point out that we must proceed carefully here. The Gospel of Philip was originally written in Greek.{27} Therefore, what the term “companion” meant in Aramaic is entirely irrelevant. Even in the Coptic translation found at Nag Hammadi, a Greek loan word (koinonos) lies behind the term translated “companion”. Darrell Bock observes that this is “not the typical . . . term for ‘wife’” in Greek.{28} Indeed, koinonos is most often used in the New Testament to refer to a “partner.” Luke uses the term to describe James and John as Peter’s business partners (Luke 5:10). So contrary to the claim of Teabing, the statement that Mary was Jesus’ companion does not at all prove that she was His wife.

But what about the following statement: “Christ loved her . . . and used to kiss her often on her mouth”?

First, this portion of the manuscript is damaged. We don’t actually know where Christ kissed Mary. There’s a hole in the manuscript at that place. Some believe that “she was kissed on her cheek or forehead since either term fits in the break.”{29} Second, even if the text said that Christ kissed Mary on her mouth, it wouldn’t necessarily mean that something sexual is in view. Most scholars agree that Gnostic texts contain a lot of symbolism. To read such texts literally, therefore, is to misread them. Finally, regardless of the author’s intention, this Gospel wasn’t written until the second half of the third century, over two hundred years after the time of Jesus.{30} So the reference to Jesus kissing Mary is almost certainly not historically reliable.

We must show our non-Christian friends that The Gospel of Philip offers insufficient evidence that Jesus was married. But what if they’ve bought into the novel’s contention that it would have been odd for Jesus to be single?

Was Jesus Married? (Part 2)

The two most educated characters in The Da Vinci Code claim that an unmarried Jesus is quite improbable. Leigh Teabing says, “Jesus as a married man makes infinitely more sense than our standard biblical view of Jesus as a bachelor” (245). Robert Langdon, Harvard professor of Religious Symbology, concurs:

Jesus was a Jew, and the social decorum during that time virtually forbid a Jewish man to be unmarried. According to Jewish custom, celibacy was condemned. . . . If Jesus were not married, at least one of the Bible’s Gospels would have mentioned it and offered some explanation for His unnatural state of bachelorhood (245).

Is this true? What if our non-Christian friends want a response to such claims?

In his excellent book Breaking The Da Vinci Code, Darrell Bock persuasively argues that an unmarried Jesus is not at all improbable.{31} Of course, it’s certainly true that most Jewish men of Jesus’ day did marry. It’s also true that marriage was often viewed as a fundamental human obligation, especially in light of God’s command to “be fruitful and multiply, and fill the earth” (Gen. 1:28). Nevertheless, by the first century there were recognized, and even lauded, exceptions to this general rule.

The first century Jewish writer, Philo of Alexandria, described the Essenes as those who “repudiate marriage . . . for no one of the Essenes ever marries a wife.”{32} Interestingly, the Essenes not only escaped condemnation for their celibacy, they were often admired. Philo also wrote, “This now is the enviable system of life of these Essenes, so that not only private individuals but even mighty kings, admiring the men, venerate their sect, and increase . . . the honors which they confer on them.”{33} Such citations clearly reveal that not all Jews of Jesus’ day considered marriage obligatory. And those who sought to avoid marriage for religious reasons were often admired rather than condemned.

It may be helpful to remind your friend that the Bible nowhere condemns singleness. Indeed, it praises those who choose to remain single to devote themselves to the work of the Lord (e.g. 1 Cor. 7:25-38). Point your friend to Matthew 19:12, where Jesus explains that some people “have renounced marriage because of the kingdom of heaven” (NIV). Notice His conclusion, “The one who can accept this should accept it.” It’s virtually certain that Jesus had accepted this. He had renounced marriage to fully devote Himself to the work of His heavenly Father. What’s more, since there was precedent in the first century for Jewish men to remain single for religious reasons, Jesus’ singleness would not have been condemned. Let your friend know that, contrary to the claims of The Da Vinci Code, it would have been completely acceptable for Jesus to be unmarried.

Did Jesus’ Earliest Followers Proclaim His Deity?

We’ve considered The Da Vinci Code‘s claim that Jesus was married and found it wanting. Mark Roberts observed “that most proponents of the marriage of Jesus thesis have an agenda. They are trying to strip Jesus of his uniqueness, and especially his deity.”{34} This is certainly true of The Da Vinci Code. Not only does it call into question Jesus’ deity by alleging that He was married, it also maintains that His earliest followers never even believed He was divine! According to Teabing, the doctrine of Christ’s deity originally resulted from a vote at the Council of Nicaea. He further asserts, “until that moment in history, Jesus was viewed by His followers as a mortal prophet . . . a great and powerful man, but a man nonetheless” (233). Did Jesus’ earliest followers really believe that He was just a man? If our non-Christian friends have questions about this, let’s view it as a great opportunity to tell them who Jesus really is!

The Council of Nicaea met in A.D. 325. By then, Jesus’ followers had been proclaiming His deity for nearly three centuries. Our earliest written sources about the life of Jesus are found in the New Testament. These first century documents repeatedly affirm the deity of Christ. For instance, in his letter to the Colossians, the apostle Paul declared, “For in Christ all the fullness of the Deity lives in bodily form” (2:9; see also Rom. 9:5; Phil. 2:5-11; Tit. 2:13). And John wrote, “In the beginning was the Word . . . and the Word was God . . . And the Word became flesh, and dwelt among us” (1:1, 14).

There are also affirmations of Jesus’ deity in the writings of the pre-Nicene church fathers. In the early second century, Ignatius of Antioch wrote of “our God, Jesus the Christ.”{35} Similar affirmations can be found throughout these writings. There’s even non-Christian testimony from the second century that Christians believed in Christ’s divinity. Pliny the Younger wrote to Emperor Trajan, around A.D. 112, that the early Christians “were in the habit of meeting on a certain fixed day . . . when they sang . . . a hymn to Christ, as to a god.”{36}

If we humbly share this information with our non-Christian friends, we can help them see that Christians believed in Christ’s deity long before the Council of Nicaea. We might even be able to explain why Christians were so convinced of His deity that they were willing to die rather than deny it. If so, we can invite our friends to believe in Jesus for themselves. “For God so loved the world that he gave his one and only Son, that whoever believes in him shall not perish but have eternal life” (John 3:16).

Notes

1. Dan Brown, The Da Vinci Code (New York: Doubleday, 2003).

2. See Dan Brown’s official website at www.danbrown.com/meet_dan/ (February 1, 2006).

3. See the Sony Pictures website at www.sonypictures.com/movies/thedavincicode/ (February 1, 2006).

4. More information is available about the series at www.probe.org.

5. Brown, The Da Vinci Code, 1.

6. For example, see Sandra Miesel, “Dismantling The Da Vinci Code,” at www.crisismagazine.com/september2003/feature1.htm and James Patrick Holding, “Not InDavincible: A Review and Critique of The Da Vinci Code,” at www.answers.org/issues/davincicode.html.

7. Philip Schaff and Henry Wace, eds., Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers (Reprint. Grand Rapids, Eerdmans, 1952), 1:549, cited in Norman Geisler and William Nix, A General Introduction to the Bible: Revised and Expanded (Chicago: Moody Press, 1986), 282.

8. For more information see Geisler and Nix, A General Introduction to the Bible, 390.

9. Lee Strobel, The Case for Christ (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan, 1998), 25.

10. Ibid., 39-40.

11. Ibid., 40.

12. Darrell Bock, Breaking The Da Vinci Code (n.p.: Thomas Nelson Publishers, 2004), 52 (pre-publication manuscript copy).

13. Ibid., 62-63. See also The Coptic Apocalypse of Peter and The Second Treatise of the Great Seth in Bart Ehrman, Lost Scriptures: Books That Did Not Make It Into The New Testament, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003), 78-86.

14. For example, The Coptic Gospel of Thomas (saying 1), in Ehrman, Lost Scriptures, 20.

15. Bock, Breaking The Da Vinci Code, 63.

16. Bart D. Ehrman, Lost Christianities: Christian Scriptures and the Battles Over Authentication (Chantilly, Virginia: The Teaching Company: Course Guidebook, part 2, 2002), 37.

17. Ehrman, Lost Scriptures, 341.

18. F.F. Bruce, “Canon,” in Dictionary of Jesus and the Gospels, Joel B. Green, Scot McKnight and I. Howard Marshall, eds. (Downers Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press, 1992), 95.

19. Ibid., 95-96.

20. Ibid., 96.

21. Darrell Bock, Breaking The Da Vinci Code (n.p. Thomas Nelson Publishers, 2004), 25-26 (pre-publication manuscript copy). I have relied heavily on Dr. Bock’s analysis in this section.

22. Ibid., 116-17.

23. Bart Ehrman, Lost Scriptures, 35.

24. Brown, The Da Vinci Code. On page 247 we read, “Sophie had not known a gospel existed in Magdalene’s words.”

25. An “apostle” can simply refer to “one sent” as an envoy or messenger. Mary was an “apostle” in this sense, since she was sent by Jesus to tell the disciples of His resurrection.

26. For more information see Bock, Breaking The Da Vinci Code, 16-18.

27. Ehrman, Lost Scriptures, 19.

28. Bock, Breaking The Da Vinci Code, 22.

29. Ibid., 21.

30. Ibid., 20.

31. In this section I have relied heavily on chapter 3 of Bock, Breaking The Da Vinci Code, pp. 40-49 (pre-publication copy).

32. Philo, Hypothetica, 11.14-17, cited in Bock, Breaking The Da Vinci Code, 43.

33. Ibid., 44.

34. Mark D. Roberts, “Was Jesus Married? A Careful Look at the Real Evidence,” at www.markdroberts.com/htmfiles/resources/jesusmarried.htm, January, 2004.

35. Ignatius of Antioch, “Ephesians,” 18:2, cited in Jack N. Sparks, ed., The Apostolic Fathers, trans. Robert M. Grant (New York: Thomas Nelson Publishers, 1978), 83.

36. Pliny, Letters, transl. by William Melmoth, rev. by W.M.L. Hutchinson (Cambridge: Harvard Univ. Press, 1935), vol. II, X:96, cited in Habermas, The Historical Jesus, 199.

© 2006 Probe Ministries

What I found more interesting, though, is the background discussion on the article. Wikipedia includes a running dialogue of the debates that determine what actually gets posted into the article, as well as what gets removed, and here the discussion can be a bit more emotional. One contributor argues that no Christian should be allowed to contribute because of their bias and commitment to the canon of the New Testament. He adds that only atheists and Jews should be allowed to participate (no bias here). The discussion also reflects the idea that as early as the beginning of the second century, the Catholic Church was conducting a massive conspiracy to keep certain texts and ideas out of the public’s hands and minds.

What I found more interesting, though, is the background discussion on the article. Wikipedia includes a running dialogue of the debates that determine what actually gets posted into the article, as well as what gets removed, and here the discussion can be a bit more emotional. One contributor argues that no Christian should be allowed to contribute because of their bias and commitment to the canon of the New Testament. He adds that only atheists and Jews should be allowed to participate (no bias here). The discussion also reflects the idea that as early as the beginning of the second century, the Catholic Church was conducting a massive conspiracy to keep certain texts and ideas out of the public’s hands and minds.

Dan Brown’s novel, The Da Vinci Code,

Dan Brown’s novel, The Da Vinci Code,