Sue Bohlin looks at suffering from a Christian perspective. Applying a biblical worldview to this difficult subject results in a distinctly different approach to suffering than our natural inclination of blame and self pity.

![]() This article is also available in Spanish.

This article is also available in Spanish.

There is no such thing as pointless pain in the life of the child of God. How this has encouraged and strengthened me in the valleys of suffering and pain! In this essay I’ll be discussing the value of suffering, an unhappy non-negotiable of life in a fallen world.

Suffering Prepares Us to Be the Bride of Christ

Among the many reasons God allows us to suffer, this is my personal favorite: it prepares us to be the radiant bride of Christ. The Lord Jesus has a big job to do, changing His ragamuffin church into a glorious bride worthy of the Lamb. Ephesians 5:26-27 tells us He is making us holy by washing us with the Word—presenting us to Himself as a radiant church, without stain or wrinkle or any other blemish. Suffering develops holiness in unholy people. But getting there is painful in the Lord’s “laundry room.” When you use bleach to get rid of stains, it’s a harsh process. Getting rid of wrinkles is even more painful: ironing means a combination of heat plus pressure. Ouch! No wonder suffering hurts!

Among the many reasons God allows us to suffer, this is my personal favorite: it prepares us to be the radiant bride of Christ. The Lord Jesus has a big job to do, changing His ragamuffin church into a glorious bride worthy of the Lamb. Ephesians 5:26-27 tells us He is making us holy by washing us with the Word—presenting us to Himself as a radiant church, without stain or wrinkle or any other blemish. Suffering develops holiness in unholy people. But getting there is painful in the Lord’s “laundry room.” When you use bleach to get rid of stains, it’s a harsh process. Getting rid of wrinkles is even more painful: ironing means a combination of heat plus pressure. Ouch! No wonder suffering hurts!

But developing holiness in us is a worthwhile, extremely important goal for the Holy One who is our divine Bridegroom. We learn in Hebrews 12:10 that we are enabled to share in His holiness through the discipline of enduring hardship. More ouch! Fortunately, the same book assures us that discipline is a sign of God’s love (Heb. 12:6). Oswald Chambers reminds us that “God has one destined end for mankind—holiness. His one aim is the production of saints.”{1}

It’s also important for all wives, but most especially the future wife of the Son of God, to have a submissive heart. Suffering makes us more determined to obey God; it teaches us to be submissive. The psalmist learned this lesson as he wrote in Psalm 119:67: “Before I was afflicted I went astray, but now I obey your word. It was good for me to be afflicted so that I might learn your decrees.”

The Lord Jesus has His work cut out for Him in purifying us for Himself (Titus 2:14). Let’s face it, left to ourselves we are a dirty, messy, fleshly people, and we desperately need to be made pure. As hurtful as it is, suffering can purify us if we submit to the One who has a loving plan for the pain.

Jesus wants not just a pure bride, but a mature one as well—and suffering produces growth and maturity in us. James 1:2-4 reminds us that trials produce perseverance, which makes us mature and complete. And Romans 5:3-4 tells us that we can actually rejoice in our sufferings, because, again, they produce perseverance, which produces character, which produces hope. The Lord is creating for Himself a bride with sterling character, but it’s not much fun getting there. I like something else Oswald Chambers wrote: “Sorrow burns up a great amount of shallowness.”{2}

We usually don’t have much trouble understanding that our Divine Bridegroom loves us; but we can easily forget how much He longs for us to love Him back. Suffering scoops us out, making our hearts bigger so that we can hold more love for Him. It’s all part of a well-planned courtship. He does know what He’s doing . . . we just need to trust Him.

Suffering Allows Us to Minister Comfort to Others Who Suffer

One of the most rewarding reasons that suffering has value is experienced by those who can say with conviction, “I know how you feel. I’ve been in your shoes.” Suffering prepares us to minister comfort to others who suffer.

Feeling isolated is one of the hardest parts of suffering. It can feel like you’re all alone in your pain, and that makes it so much worse. The comfort of those who have known that same pain is inexpressible. It feels like a warm blanket being draped around your soul. But in order for someone to say those powerful words—”I know just how you feel because I’ve been there”—that person had to walk through the same difficult valley first.

Ray and I lost our first baby when she was born too prematurely to survive. It was the most horrible suffering we’ve ever known. But losing Becky has enabled me to weep with those who weep with the comforting tears of one who has experienced that deep and awful loss. It’s a wound that—by God’s grace—has never fully healed so that I can truly empathize with others out of the very real pain I still feel. Talking about my loss puts me in touch with the unhealed part of the grief and loss that will always hurt until I see my daughter again in heaven. One of the most incredibly comforting things we can ever experience is someone else’s tears for us. So when I say to a mother or father who has also lost a child, “I hurt with you, because I’ve lost a precious one too,” my tears bring warmth and comfort in a way that someone who has never known that pain cannot offer.

One of the most powerful words of comfort I received when we were grieving our baby’s loss was from a friend who said, “Your pain may not be about just you. It may well be about other people, preparing you to minister comfort and hope to someone in your future who will need what you can give them because of what you’re going through right now. And if you are faithful to cling to God now, I promise He will use you greatly to comfort others later.” That perspective was like a sweet balm to my soul, because it showed me that my suffering was not pointless.

There’s another aspect of bringing comfort to those in pain. Those who have suffered tend not to judge others experiencing similar suffering. Not being judged is a great comfort to those who hurt. When you’re in pain, your world narrows down to mere survival, and it’s easy for others to judge you for not “following the rules” that should only apply to those whose lives aren’t being swallowed by the pain monster.

Suffering often develops compassion and mercy in us. Those who suffer tend to have tender hearts toward others who are in pain. We can comfort others with the comfort that we have received from God (2 Cor. 1:4) because we have experienced the reality of the Holy Spirit being there for us, walking alongside us in our pain. Then we can turn around and walk alongside others in their pain, showing the compassion that our own suffering has produced in us.

Suffering Develops Humble Dependence on God

Marine Corps recruiter Randy Norfleet survived the Oklahoma City bombing despite losing 40 percent of his blood and needing 250 stitches to close his wounds. He never lost consciousness in the ambulance because he was too busy praying prayers of thanksgiving for his survival. When doctors said he would probably lose the sight in his right eye, Mr. Norfleet said, “Losing an eye is a small thing. Whatever brings you closer to God is a blessing. Through all this I’ve been brought closer to God. I’ve become more dependent on Him and less on myself.”{3}

Suffering is excellent at teaching us humble dependence on God, the only appropriate response to our Creator. Ever since the fall of Adam, we keep forgetting that God created us to depend on Him and not on ourselves. We keep wanting to go our own way, pretending that we are God. Suffering is powerfully able to get us back on track.

Sometimes we hurt so much we can’t pray. We are forced to depend on the intercession of the Holy Spirit and the saints, needing them to go before the throne of God on our behalf. Instead of seeing that inability to pray as a personal failure, we can rejoice that our perception of being totally needy corresponds to the truth that we really are that needy. 2 Corinthians 1:9 tells us that hardships and sufferings happen “so that we might not rely on ourselves but on God, who raises the dead.”

Suffering brings a “one day at a time-ness” to our survival. We get to the point of saying, “Lord, I can only make it through today if You help me . . . if You take me through today . . . or the next hour . . . or the next few minutes.” One of my dearest friends shared with me the prayer from a heart burning with emotional pain: “Papa, I know I can make it through the next fifteen minutes if You hold me and walk me through it.” Suffering has taught my friend the lesson of total, humble dependence on God.

As painful as it is, suffering strips away the distractions of life. It forces us to face the fact that we are powerless to change other people and most situations. The fear that accompanies suffering drives us to the Father like a little kid burying his face in his daddy’s leg. Recognizing our own powerlessness is actually the key to experience real power because we have to acknowledge our dependence on God before His power can flow from His heart into our lives.

The disciples experienced two different storms out on the lake. The Lord’s purpose in both storms was to train them to stop relying on their physical eyes and use their spiritual eyes. He wanted them to grow in trust and dependence on the Father. He allows us to experience storms in our lives for the same purpose: to learn to depend on God.

I love this paraphrase of Romans 8:28: “The Lord may not have planned that this should overtake me, but He has most certainly permitted it. Therefore, though it were an attack of an enemy, by the time it reaches me, it has the Lord’s permission, and therefore all is well. He will make it work together with all life’s experiences for good.”

Suffering Displays God’s Strength Through Our Weakness

God never wastes suffering, not a scrap of it. He redeems all of it for His glory and our blessing. The classic Scripture for the concept that suffering displays God’s strength through our weakness is found in 2 Corinthians 12:8-10, where we learn that God’s grace is sufficient for us, for His power is perfected in weakness. Paul said he delighted in weaknesses, hardships, and difficulties “for when I am weak, then I am strong.”

Our culture disdains weakness, but our frailty is a sign of God’s workmanship in us. It gets us closer to what we were created to be—completely dependent on God. Several years ago I realized that instead of despising the fact that polio had left me with a body that was weakened and compromised, susceptible to pain and fatigue, I could choose to rejoice in it. My weakness made me more like a fragile, easily broken window than a solid brick wall. But just as sunlight pours through a window but is blocked by a wall, I discovered that other people could see God’s strength and beauty in me because of the window-like nature of my weakness! Consider how the Lord Jesus was the exact representation of the glory of the Father—I mean, He was all window and no walls! He was completely dependent on the Father, choosing to become weak so that God’s strength could shine through Him. And He was the strongest person the world has ever seen. Not His own strength; He displayed the Father’s strength because of that very weakness.

The reason His strength can shine through us is because we know God better through suffering. One wise man I heard said, “I got theology in seminary, but I learned reality through trials. I got facts in Sunday School, but I learned faith through trusting God in difficult circumstances. I got truth from studying, but I got to know the Savior through suffering.”

Sometimes our suffering isn’t a consequence of our actions or even someone else’s. God is teaching other beings about Himself and His loved ones—us—as He did with Job. The point of Job’s trials was to enable heavenly beings to see God glorified in Job. Sometimes He trusts us with great pain in order to make a point, whether the intended audience is believers, unbelievers, or the spirit realm. Quadriplegic Joni Eareckson Tada, no stranger to great suffering, writes, “Whether a godly attitude shines from a brain-injured college student or from a lonely man relegated to a back bedroom, the response of patience and perseverance counts. God points to the peaceful attitude of suffering people to teach others about Himself. He not only teaches those we rub shoulders with every day, but He instructs the countless millions of angels and demons. The hosts in heaven stand amazed when they observe God sustain hurting people with His peace.”{4}

I once heard Charles Stanley say that nothing attracts the unbeliever like a saint suffering successfully. Joni Tada said, “You were made for one purpose, and that is to make God real to those around you.”{5} The reality of God’s power, His love, and His character are made very, very real to a watching world when we trust Him in our pain.

Suffering Gets Us Ready for Heaven

Pain is inevitable because we live in a fallen world. 1 Thessalonians 3:3 reminds us that we are “destined for trials.” We don’t have a choice whether we will suffer–our choice is to go through it by ourselves or with God.

Suffering teaches us the difference between the important and the transient. It prepares us for heaven by teaching us how unfulfilling life on earth is and helping us develop an eternal perspective. Suffering makes us homesick for heaven.

Deep suffering of the soul is also a taste of hell. After many sleepless nights wracked by various kinds of pain, my friend Jan now knows what she was saved from. Many Christians only know they’re saved without grasping what it is Christ has delivered them from. Jan’s suffering has given her an appreciation of the reality of heaven, and she’s been changed forever.

I have an appreciation of heaven gained from a different experience. As my body weakens from the lifelong impact of polio, to be honest, I have a deep frustration with it that makes me grateful for the perfect, beautiful, completely working resurrection body waiting for me on the other side. My husband once told me that heaven is more real to me than anyone he knows. Suffering has done that for me. Paul explained what happens in 2 Corinthians 4:16-18:

“Though outwardly we are wasting away, yet inwardly we are being renewed day by day. For our light and momentary troubles are achieving for us an eternal glory that far outweighs them all. So we fix our eyes not on what is seen, but on what is unseen, for what is seen is temporary, but what is unseen is eternal.”

One of the effects of suffering is to loosen our grasp on this life, because we shouldn’t be thinking that life in a fallen world is as wonderful as we sometimes think it is. Pastor Dick Bacon once said, “If this life were easy, we’d just love it too much. If God didn’t make it painful, we’d never let go of it.” Suffering reminds us that we live in an abnormal world. Suffering is abnormal–our souls protest, “This isn’t right!” We need to be reminded that we are living in the post-fall “Phase 2.” The perfect Phase 1 of God’s beautiful, suffering-free creation was ruined when Adam and Eve fell. So often, people wonder what kind of cruel God would deliberately make a world so full of pain and suffering. They’ve lost track of history. The world God originally made isn’t the one we experience. Suffering can make us long for the new heaven and the new earth where God will set all things right again.

Sometimes suffering literally prepares us for heaven. Cheryl’s in-laws, both beset by lingering illnesses, couldn’t understand why they couldn’t just die and get it over with. But after three long years of holding on, during a visit from Cheryl’s pastor, the wife trusted Christ on her deathbed and the husband received assurance of his salvation. A week later the wife died, followed in six months by her husband. They had continued to suffer because of God’s mercy and patience, who did not let them go before they were ready for heaven.

Suffering dispels the cloaking mists of inconsequential distractions of this life and puts things in their proper perspective. My friend Pete buried his wife a few years ago after a battle with Lou Gehrig’s disease. One morning I learned that his car had died on the way to church, and I said something about what a bummer it was. Pete just shrugged and said, “This is nothing.” That’s what suffering will do for us. Trials are light and momentary afflictions . . . but God redeems them all.

Notes

1. Oswald Chambers, Our Utmost for His Highest, September 1.

2. Chambers, June 25.

3. National and International Religion Report, Vol. 9:10, May 1, 1995, 1

4. Joni Eareckson Tada, When Is It Right to Die? (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1992), 122.

5. Tada, 118.

©2000 Probe Ministries, updated 2018

I remember one time a couple of months into my new life, discovering a different kind of fellowship with other Christ-followers and a love for God’s word as I started being taught the Bible and learning to teach others what I was learning, wondering if this cool new life would last or if it was just some sort of fad. I didn’t know that God was transforming me, giving me a taste for His life and His kingdom that would spoil me for any counterfeit the world had to offer. He opened my eyes to be aware of the spiritual realm, not just the physical realm I lived in, and enlarged my understanding to include the Big Picture of life on earth and in eternity. I learned that my life wasn’t about me at all, it was about Jesus, and because He loved me, He had drawn me into His life, His circle of delight and fellowship with His Father and His Spirit—that I was now included into the “holy hug” of Father, Son and Spirit who had adopted me, and I was now a daughter of the King—which makes me a forever princess! Forty years later, I still revel in that gift, and I love to pull out a tiara and pop it on my head when I’m sharing my story of grace with people.

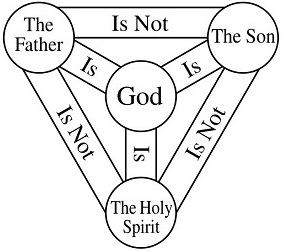

I remember one time a couple of months into my new life, discovering a different kind of fellowship with other Christ-followers and a love for God’s word as I started being taught the Bible and learning to teach others what I was learning, wondering if this cool new life would last or if it was just some sort of fad. I didn’t know that God was transforming me, giving me a taste for His life and His kingdom that would spoil me for any counterfeit the world had to offer. He opened my eyes to be aware of the spiritual realm, not just the physical realm I lived in, and enlarged my understanding to include the Big Picture of life on earth and in eternity. I learned that my life wasn’t about me at all, it was about Jesus, and because He loved me, He had drawn me into His life, His circle of delight and fellowship with His Father and His Spirit—that I was now included into the “holy hug” of Father, Son and Spirit who had adopted me, and I was now a daughter of the King—which makes me a forever princess! Forty years later, I still revel in that gift, and I love to pull out a tiara and pop it on my head when I’m sharing my story of grace with people. Even though it’s short, this definition is both a mouthful and a mind full. But let’s settle on four basic concepts before we move on to the implications. At the heart of the definition of the Blessed Trinity we have: one God, three Persons, who are coequal and coeternal. With this sketch in place, then, we are ready to move out and survey the importance of the Trinity with respect to the Christian worldview and its practical aspects for the Christian life. At the end of our discussion I truly hope that we can affirm together our love for the Trinity.

Even though it’s short, this definition is both a mouthful and a mind full. But let’s settle on four basic concepts before we move on to the implications. At the heart of the definition of the Blessed Trinity we have: one God, three Persons, who are coequal and coeternal. With this sketch in place, then, we are ready to move out and survey the importance of the Trinity with respect to the Christian worldview and its practical aspects for the Christian life. At the end of our discussion I truly hope that we can affirm together our love for the Trinity.