Kerby Anderson provides a summary of how mankind has viewed the world from the Romans until today. This summary provides us a perspective against which to compare and contrast a Christian, biblical worldview based on New Testament principles.

Roman Worldview

On the Probe Web site we often talk about worldviews. I want to explain how the worldviews we talk about developed through history. We will be using as our foundation an excellent book written by Professor Glenn Sunshine whom I have met and also had the privilege of interviewing. His book is Why You Think the Way You Do: The Story of Western Worldviews from Rome to Home.{1}

Glenn Sunshine is a member of the church that Jonathan Edwards attended when he was at Yale. Professor Sunshine gave a lecture about Jonathan Edward’s worldview at a conference they held, and Chuck Colson invited him to teach with the Centurions program. He gave a talk about “How We Got Here” and then later turned it into Why You Think the Way You Do.

Glenn Sunshine is a member of the church that Jonathan Edwards attended when he was at Yale. Professor Sunshine gave a lecture about Jonathan Edward’s worldview at a conference they held, and Chuck Colson invited him to teach with the Centurions program. He gave a talk about “How We Got Here” and then later turned it into Why You Think the Way You Do.

Since we will be talking about worldview, it would be good to begin with Glenn Sunshine’s definition. “A worldview is the framework you use to interpret the world and your place in it.”{2} You do not need to be a philosopher to have a worldview. All of us have a worldview.

Although Glenn Sunshine begins with the worldview of the Roman world, he quickly takes us back to neo-Platonism. It was the religion and philosophy based upon Plato’s ideas. Neo-Platonism was the belief that the fundamental ground of reality is non-physical. Instead it is found in the world of ideas (and is known as idealism). These ideas cast shadows that cast other shadows until they arrive at the physical world.

According to this worldview, the whole universe exists as a hierarchy. The spiritual is superior to the physical. This provides a scale of values for the world, but also provides a scale for humanity. In other words, those who are superior should rule over those who are inferior because they have demonstrated their ability to rule or conquer.

This view of hierarchy led to the idea of the father having superiority over all members of the family. It led to the idea that men are superior to women. It led to the idea that the emperor should rule and be worshipped. And it led to the idea that slaves are inferior to free people and nothing more than “living tools.”{3}

This explains not only the success of Rome but also its ugly underside. Essentially there are two pictures of Rome: “the glittering empire and the rotten core.”{4}

In Rome, human life did not have much value. While it is true that Romans abandoned human sacrifice, they engaged in other practices equally abhorrent. “They picked up the Etruscan practice of having people fight to the death in games in honor of the dead.”{5}

Slavery provided the economic foundation for the empire. Abortion and infanticide were regularly practiced. “Roman families would usually keep as many healthy sons as they had and only one daughter; the rest were simply discarded.”{6} And Roman law required that a father kill any visibly deformed child.

Transformation of the Pagan World

How did Christianity transform the pagan world? In AD 303, the Roman emperor Diocletian began a severe persecution of Christians. But because Christians were faithful and even willing to go to their deaths for their beliefs, their credibility increased. Eventually they were accepted and allowed to exercise their faith. Constantine even legalized the Christian faith by AD 313.

Once that took place, Christian ideas were allowed to percolate through society. One of the most important ideas was that human beings are created in the image of God. This idea has a profound impact. First, it meant that people are fundamentally equal to each other. No longer were there grounds for saying that some people are superior to others. In fact, “Christians were the first people in history to oppose slavery systematically.”{7}

Christians (who believed that all are created in the image of God) treated the sick differently. They believed that even those who were deathly ill still deserved care. Dionysius of Alexandria reported that Christians (often at great risk to their own lives) “visited the sick fearlessly and ministered to them continually.”{8} They would rescue babies abandoned in an act of infanticide. They would oppose abortion.

In economics, we can also see the influence of Christianity. The idea that God created the universe and then rested showed that God worked. That would mean that human beings (made in the image of God) are expected to work as well. God gave Adam and Eve intellectual work (in naming the animals) and physical work (in tending the Garden). Contrast this with the Roman world where physical work was seen as something that only slaves would do. Christians saw labor as something that was intrinsically valuable.

Labor is good; drudgery is bad. Drudgery is a result of the Fall (Genesis 3). So Christians were the first to develop technology to remove drudgery from work. Other civilizations had technology, but the West uniquely applied such things as water power to make work more valuable and worthwhile by eliminating the drudgery and repetitive nature of certain tasks.

Property rights were also well-developed during this period. “The medieval world under the influence of Christianity has a much stronger emphasis on property rights than other cultures had.”{9}

These ideas come from a biblical worldview and began to be developed during the Middle Ages. This led to a complete transformation of western society and set it on a trajectory to our modern world.

Christianity and Politics

Glenn Sunshine points out that in the West, the dynamic between church and state is unique. Christianity was originally a persecuted minority religion. Even when Christianity was declared a legal religion, the church did not depend upon the state. So the question of the relationship between church and state has been an open question.

During the Middle Ages, two men helped shape political thinking. The first was Augustine, who described two realms: the City of God and the City of Man. He argued that human government is the result of sin. He believed that it is based upon selfishness. Government itself is corruption. In the absence of government, anarchy reigns. So government is a necessary evil.

The City of God is different in that it is not based upon force or coercion. It is based upon love, charity, and repentance. That doesn’t mean that the City of Man and the City of God cannot work together. But overall, Augustine had a more pessimistic view of government.

Aristotle had a different view of government. As people in the Middle Ages began to rediscover Aristotle, they began to develop a different view of government. They saw government as a necessary institution that God has placed in the world. It had positive and legitimate functions.

Aristotle believed that government had a more positive role in society. But the Christian theologians had to also deal with the problem of original sin. They wanted to find a way to prevent original sin from corrupting the government. The tension between these two views is what drives the discussion of western political theory.

Sunshine notes that “another check on civil government involved the idea of rights.”{10} We normally associate the idea of rights, especially inalienable rights, with eighteenth century political theorists. However, John Locke’s idea that we have inalienable right to life, liberty, and property is already found in the writings of medieval theologians. The basis for this is a belief that all are created in the image of God. Therefore, all of us have a number of natural rights that the state cannot remove. Natural law was the idea that God wove moral laws into the fabric of the universe.

There also was the belief that there should be limitations on the jurisdiction of civil government and church government. One example is the Magna Carta, that stated that the English church was to be free and its liberties unimpaired by the crown.

The Renaissance and Enlightenment

What about the transformation into the modern world? In the early modern period, starting with the Renaissance in the fifteenth century to the seventeenth century, there are a whole series of events that shook the worldview consensus that developed in the Middle Ages.

Previously there were certain beliefs about truth: (1) that truth was absolute, (2) that truth is knowable to the human mind, and (3) that truth is necessary for society (a society could not be based upon a lie). The best good guide for truth would be the great civilizations of the past that lasted for so long and thus must have been based upon truth.

The idea was to go to the past to find truth. During the Renaissance scholars were very successful in collecting manuscripts and finding ancient sources. Unfortunately, they found so many sources that they discovered there was not a coherent perspective. The ancient writers disagreed with each other. In a sense, the Renaissance was a victim of its own success. There was too much information. The more ancient sources they found, the less likely they would find agreement in the perspectives. Once it became obvious that this grand synthesis was not possible, the entire purpose of intellectual activity was thrown into question.

Then there were the wars of the Reformation in which various factions fought over who was the true follower of the prince of peace. The devastation of the religious wars left many people wondering if there really was religious certainty. No longer was the question “is Christianity true” but rather “which Christianity is true?” Now you had a multiplicity of options that left people confused. This also generated questions about the role of religion in society.

Then you also had the discovery of the New World and whole people groups that had never heard the gospel. Some began to ask questions like: Is it fair of God to send them all to hell because they had never heard of Christianity? Or, in light of biblical history, where did they come from? How do these people fit with the story of Noah? These discoveries called into question biblical morality and biblical history.

Also, people started using a new way of looking at knowledge. They began to use the scientific method to evaluate everything. This begins a significant shift in how we understand the world. There is a movement away from certainty toward probability. There is also a movement away from studying ancient authors toward scientific experimentation.

In the modern world, therefore, truth is not found in the past but in the present and future. With this is also questioning of biblical authority.

The Modern World and Christianity

Let me conclude by talking about our modern world and how Christians should respond. Sunshine concludes his book with chapters on “Modernity and Its Discontents” and “The Decay of Modernity.” Essentially the modern world has left humans with a loss of truth, certainty, and meaning in life. “Materialism provides a ready answer to the question of the meaning and purpose of life: there is none.”{11} From a Darwinian perspective, our only purpose is to pass our genes on to the next generation.

This rejection of spirituality and meaning has ushered in various other worldviews as alternatives. These would be such worldviews as postmodernism, neo-paganism, and the New Age Movement. Sunshine argues that in many ways we have been catapulted back to Rome.

Like Rome we value toleration as the supreme virtue. Rome believed that toleration was important because it kept the empire together. If you go beyond the lines of toleration, you are persecuted. This is similar to the mindset today. The highest value in a postmodern world is toleration. Toleration so defined means that we will embrace any and all lifestyles people may choose.

The Romans lived in an oversexed society.{12} So do we. Rome practiced abortion. So does our society. Rome was antinatal and made a deliberate attempt to prevent pregnancy. They focused on sexual enjoyment and did not want to bother with kids. In our modern world, birthrates in most of the western democracies are plummeting.

Western civilization is a product of ancient Roman civilization plus Christianity. Sunshine argues that once you removed Christianity, modern society reverted back to Roman society and a recovery of the ancient pagan worldview.

So how should Christians live in this world? Of course, we should live out a biblical worldview. Every generation is called to live faithfully to the gospel, and our generation is no exception.

This is especially important today since we are facing a society that is not willing to accept biblical ideas. In many ways, we face a challenge similar to the early church, though not as daunting. From history we can see that the early church did live faithfully and transformed the Roman world. Christians produced a totally new civilization: western culture. By living faithfully before the watching world, we will increase our credibility and earn the respect from those who are around us by living in accordance with biblical principles.

Notes

1. Glenn Sunshine, Why You Think the Way You Do: The Story of Western Worldviews from Rome to Home (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2009).

2. Ibid., 13.

3. Ibid., 31

4. Ibid., 20

5. Ibid., 30

6. Ibid., 33-34

7. Ibid., 43

8. Ibid., 44

9. Ibid., 76

10. Ibid., 91

11. Ibid., 177

12. Ibid., 33

© 2010 Probe Ministries

A recent book by Robert Bowman and Ed Komoszewski titled Putting Jesus in His Place is a great confidence builder for those wrestling with this key doctrine. The book offers five lines of evidence with deep roots in the biblical material. The book is organized around the acronym H.A.N.D.S. It argues that the New Testament teaches that Jesus deserves the honors only due to God, He shares the attributes that only God possesses, He is given names that can only be given to God, He performs deeds that only God can perform, and finally, He possesses a seat on the throne of God.

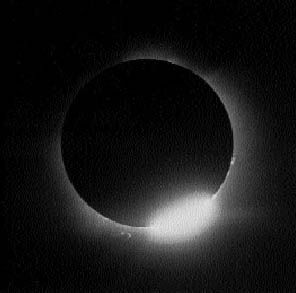

A recent book by Robert Bowman and Ed Komoszewski titled Putting Jesus in His Place is a great confidence builder for those wrestling with this key doctrine. The book offers five lines of evidence with deep roots in the biblical material. The book is organized around the acronym H.A.N.D.S. It argues that the New Testament teaches that Jesus deserves the honors only due to God, He shares the attributes that only God possesses, He is given names that can only be given to God, He performs deeds that only God can perform, and finally, He possesses a seat on the throne of God. During an eclipse, the heavens declare the glory of God by allowing us to see things about the sun we wouldn’t be able to observe any other way, beautiful and gloriously resplendent. Just before totality we can see “Baily’s Beads.” Only seen during an eclipse, bright “beads” appear at the edge of the moon where the sun is shining through lunar valleys, a feature of the moon’s rugged landscape. This is followed by the “diamond ring” effect, where the brightness of the sun radiates as a thin band around the circumference of the moon, and the last moments of the sun’s visibility explode like a diamond made of pure light. After the minutes of totality, the diamond ring effect appears again on the opposite side of the moon as the first rays of the sun flare brilliantly. These sky-jewelry phenomena are so outside of mankind’s control that witnessing them stirs our spirits (even on YouTube!) with the truth of Romans 1:20—”God’s invisible qualities—his eternal power and divine nature—have been clearly seen, being understood from what has been made, so that people are without excuse.”

During an eclipse, the heavens declare the glory of God by allowing us to see things about the sun we wouldn’t be able to observe any other way, beautiful and gloriously resplendent. Just before totality we can see “Baily’s Beads.” Only seen during an eclipse, bright “beads” appear at the edge of the moon where the sun is shining through lunar valleys, a feature of the moon’s rugged landscape. This is followed by the “diamond ring” effect, where the brightness of the sun radiates as a thin band around the circumference of the moon, and the last moments of the sun’s visibility explode like a diamond made of pure light. After the minutes of totality, the diamond ring effect appears again on the opposite side of the moon as the first rays of the sun flare brilliantly. These sky-jewelry phenomena are so outside of mankind’s control that witnessing them stirs our spirits (even on YouTube!) with the truth of Romans 1:20—”God’s invisible qualities—his eternal power and divine nature—have been clearly seen, being understood from what has been made, so that people are without excuse.” A total solar eclipse offers so much more, though, than Baily’s Beads and the Diamond Ring. At the moment of totality, the pinkish arc of the sun’s chromosphere (the part of the sun’s atmosphere just above the surface) suddenly “turns on” as if an unseen hand flips a switch. I knew God is very fond of pink because of how He paints glorious sunrises and sunsets in Earth’s skies, but those fortunate enough to see a total eclipse can see how He radiates pinkness from the sun itself! The heavens declare the glory of God!

A total solar eclipse offers so much more, though, than Baily’s Beads and the Diamond Ring. At the moment of totality, the pinkish arc of the sun’s chromosphere (the part of the sun’s atmosphere just above the surface) suddenly “turns on” as if an unseen hand flips a switch. I knew God is very fond of pink because of how He paints glorious sunrises and sunsets in Earth’s skies, but those fortunate enough to see a total eclipse can see how He radiates pinkness from the sun itself! The heavens declare the glory of God! For the few minutes of totality, the naked eye can see the sun’s lovely corona (Latin for crown) streaming out from the sun. We can’t see the corona except during an eclipse because looking straight at the sun for even a few seconds causes eye damage, and because the sun’s ball of fire overwhelms the (visually) fragile corona. This is another way that an eclipse allows us to see how the heavens declare the glory of God.

For the few minutes of totality, the naked eye can see the sun’s lovely corona (Latin for crown) streaming out from the sun. We can’t see the corona except during an eclipse because looking straight at the sun for even a few seconds causes eye damage, and because the sun’s ball of fire overwhelms the (visually) fragile corona. This is another way that an eclipse allows us to see how the heavens declare the glory of God.

What made the Romans such a formidable force? Discipline and adaptability. Being able to march long distances and maneuver across a variety of terrain. Timing and distance determine the victor of any confrontation. To do this, they needed shoes that were durable and able to grip the ground firmly.

What made the Romans such a formidable force? Discipline and adaptability. Being able to march long distances and maneuver across a variety of terrain. Timing and distance determine the victor of any confrontation. To do this, they needed shoes that were durable and able to grip the ground firmly. We are also told to take up the Shield of Faith (Ephesians 6:16) to extinguish the flaming arrows of the evil one. The favored shield in the time Ephesians was written was the Roman scutum, a large shield that protected most of the soldier’s body, enabling the Romans to protect both themselves and each other in tight formations without sacrificing their defense when fighting in looser formations. Most deaths in ancient battles occurred after, during, and after a rout. Therefore projectiles were used to disrupt and to instill fear before the two sides met in melee. Standing firm against hails of projectiles was key to surviving the battle.

We are also told to take up the Shield of Faith (Ephesians 6:16) to extinguish the flaming arrows of the evil one. The favored shield in the time Ephesians was written was the Roman scutum, a large shield that protected most of the soldier’s body, enabling the Romans to protect both themselves and each other in tight formations without sacrificing their defense when fighting in looser formations. Most deaths in ancient battles occurred after, during, and after a rout. Therefore projectiles were used to disrupt and to instill fear before the two sides met in melee. Standing firm against hails of projectiles was key to surviving the battle. Finally, Ephesians 6:17 refers to the Sword of the Spirit, or the word of God. In conjunction with the scutum was the gladius, a short sword primarily used for thrusting and short cuts. It was the legionary’s primary weapon. After throwing their pila (specialized javelins) to disrupt the enemy formation, the Romans drew their swords and closed the distance to engage in hand-to-hand fighting. Their armor and discipline enabled them to weather the brutal melee far better than their opponents. Ideally, this caused the enemy to rout.

Finally, Ephesians 6:17 refers to the Sword of the Spirit, or the word of God. In conjunction with the scutum was the gladius, a short sword primarily used for thrusting and short cuts. It was the legionary’s primary weapon. After throwing their pila (specialized javelins) to disrupt the enemy formation, the Romans drew their swords and closed the distance to engage in hand-to-hand fighting. Their armor and discipline enabled them to weather the brutal melee far better than their opponents. Ideally, this caused the enemy to rout.