Dr. Michael Gleghorn addresses how the Old Testament treats body and soul. What does it have to say about the nature and destiny of humanity?

The Breath of Life

The worldview of Naturalism tells us that the natural world is all that exists. There is nothing “above” or “beyond” this. Space, time, matter, and energy, the sort of things studied in physics, are the only material entities. You are your body, and nothing more. You do not have an immaterial mind or soul that is (in some sense) distinct from your body. You are your body. And when your body dies, you will cease to exist.

But is this true? In this article we address body and soul in the Old Testament. What does the Old Testament have to say about the nature and destiny of humanity?

But is this true? In this article we address body and soul in the Old Testament. What does the Old Testament have to say about the nature and destiny of humanity?

Let’s begin with the creation of Adam. Consider the way in which the Bible describes this event: “Then the Lord God formed the man of dust from the ground and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life, and the man became a living creature” (Genesis 2:7). Note that Adam is created from two distinct elements: the dust of the ground and the breath of life. His body is composed of “dust from the ground.” But he doesn’t become “a living creature” until God takes the second step of breathing “the breath of life” into his nostrils. Although this description may well be metaphorical in certain respects, it seems evident that God must add “the breath of life” for Adam to become a living human being.

Here’s another observation. Notice that Adam doesn’t suddenly spring to life once the dust of the earth has been ordered in a particular way. Apparently, human personality does not spontaneously emerge once God has formed the dust of the ground into a human body.{1} Merely ordering the physical elements into a human body is not enough (at least, at this initial stage of human development) to get a human person. That second step, in which God breathes the breath of life into the already formed body, is also necessary.

So what are we to make of this? Does Genesis give us a picture of a human being as a body-soul composite? At this point, such a conclusion would be premature. We have not yet considered what a soul is, nor whether “the breath of life” in some way corresponds to, or produces, it. One thing seems clear, however. The Bible seems to suggest that human beings are more than just physical bodies. There appears to be an additional component to our nature, and we need to spend some time gaining a better understanding of what that is.

Surviving the Death of the Body

The book of Genesis briefly describes the death of Jacob’s wife, Rachel, as she gave birth to their son, Benjamin.{2} We read that “as her soul was departing (for she died),” she named her son (Genesis 35:18).

How are we to understand the phrase, “as her soul was departing”? In Hebrew, the word here translated “soul” is the term nephesh. Part of the difficulty in understanding the phrase is that nephesh can be used in a variety of ways. According to the Christian philosopher J. P. Moreland, “The term nephesh . . . is used primarily of human beings, though it is also used of animals (Genesis 1:20; 9:10; 24:30) and of God Himself (Judges 10:16; Isaiah 1:14).”{3}

Depending on the context, the term might refer to a part of the body, like the neck (Psalm 105:18) or throat (Isaiah 5:14). It can also be used of the principle of life, as in Leviticus 17:11: “the life [that is, nephesh] of the flesh is in the blood.” Strangely, however, it can also refer to a dead human body (Numbers 5:2; 6:11). Moreover, it can be used of various psychological aspects of human experience, like emotions or desires (Proverbs 21:10; Isaiah 26:9; Micah 7:1). Finally, there are also indications that the

term can refer to what might be called the “soul”—the immaterial component of a human being in which one’s personal identity is located.{4}

So when we read that Rachel’s “soul was departing,” does this simply mean that she was dying, that the “principle of life” (which had sustained her to this point) was departing? Or could it mean that her “soul,” an immaterial component of her being encompassing her personal identity, was departing? In other words, is this verse merely telling us that Rachel’s body was dying, or is it also telling us that, as her body was dying, her soul was leaving her body (possibly to continue its existence elsewhere)?

If we examine other passages of Scripture, we see evidence that the human soul continues to exist after the death of the body. Consider Psalm 49:15: “But God will ransom my soul from the power of Sheol, for he will receive me.” In Hebrew thought, Sheol was the place of the dead, somewhat like the Greek conception of Hades.{5} In this passage, the Psalmist expresses confidence that God will ransom his “soul” from the place of the dead and receive the Psalmist to himself. This view of the soul becomes even clearer when we examine what the Old Testament has to say about the afterlife.

The Place of the Dead

In the Old Testament the place of the dead is called Sheol. Of course, in some places the term simply refers to the grave. Nevertheless, according to John Cooper, “There is virtual consensus that the Israelites did believe in some sort of ethereal existence after death in a place called Sheol.”{6} What sort of place was this?

Job describes it as a place of “ease,” where “the wicked cease from troubling” and “the weary are at rest” (3:13, 17-18). That sounds pretty good! However, it’s also described as a place of “darkness” and “the land of forgetfulness” (Psalm 88:12), a place where not much is happening. As the author of Ecclesiastes puts it: “There is no work or thought or knowledge or wisdom in Sheol, to which you are going” (9:10). Hence, J. P. Moreland observes, “Life in Sheol is often depicted as lethargic and inactive.”{7}

But there are exceptions. Consider the case of Saul and the medium of Endor (1 Samuel 28). The prophet Samuel had died, and Saul is preparing to go to war against the Philistines (vv. 1-4). After seeing the

Philistine army, however, Saul is afraid (v. 5). He inquires of the Lord, but the Lord does not answer him (v. 6). In desperation, Saul seeks out a medium at Endor, and asks her to call up Samuel from the dead (vv. 7-11). Incredibly, the plan works, and Samuel actually makes an appearance (vv. 12-14).

Saul inquires of Samuel, but Samuel essentially rebukes Saul (vv. 15-16), reminding Saul of his prior disobedience. He tells Saul that Israel will be defeated by the Philistines and informs him that “Tomorrow you and your sons shall be with me” (vv. 18-19). It’s a fascinating story, but we must not lose sight of what (for us) is the main point.

Notice that Samuel, who had previously died, and whose body had been buried (v. 3), retains his personal identity in the shadowy underworld of Sheol. He still knows who he is, remembers Saul, and can function as the Lord’s prophet. Although Samuel is pictured in the story as “an old man . . . wrapped in a robe” (v. 14), Moreland reminds us that the Bible often uses such imagery “in a nonliteral way to describe immaterial, invisible realities.”{8} Regardless, the Old Testament teaches that human beings continue to exist after the death of the body. Moreover, the righteous express a hope that God will

rescue their souls even from Sheol.

Redemption from Sheol

The Old Testament pictures all those who die as going initially to Sheol, the place of the dead. However, it also intimates a hope for the righteous even “beyond the grave.” As John Cooper notes, “Several Psalms read most naturally as confessing a steadfast if unspecified trust in God beyond death.”{9}

Consider Psalm 49. The psalmist observes that all people die. Sooner or later each person’s life ends in death (vv. 5-12). But for the psalmist that is not the end of the story. Though he knows that this life

will end with the death of his body, he nonetheless confidently proclaims: “But God will ransom my soul from the power of Sheol, for he will receive me” (v. 15).

Or consider Psalm 73. The psalmist begins by confessing that he was “envious of the arrogant” and “wicked” (v. 3). However, as he contemplated that their end is “destruction,” his hope in God was renewed (vv. 17-24).

Although the psalmist recognized that he, too, would die, he declares his hope in God: “My flesh and my heart may fail, but God is the strength of my heart and my portion forever” (v. 26). After surveying such

material, one Old Testament scholar notes that before God “there is not only the alternative between this life and the shadow existence in the world of the dead; there is a third possibility—a permanent, living fellowship with him.”{10} This third possibility was the confident hope of the psalmists.

Of course, if we’re going to be fair, we must also agree with C. S. Lewis, who observes that throughout much of the Old Testament, belief in the afterlife held virtually no “religious importance” whatever.{11} What mattered to the ancient Israelite was life on this earth. It is here that we can enjoy fellowship with family, friends—and God.

So why did God reveal so little to the ancient Israelites about the nature of the afterlife? Lewis suggests that God may have wanted His people to come to love Him primarily as an end in itself—and not for any

rewards he might bestow in the afterlife. If one becomes friends with God in this life, then one will naturally fear to lose this relationship in death. And at this point, God can step in with the “good news” that friendship with Him can continue beyond death.{12} Indeed, God even promised to raise the bodies of his people from the dead, to continue their friendship with him on a new earth!

The Resurrection of the Body

The resurrection of the body is a doctrine that many believers rarely think about. Yet this doctrine is not only taught throughout the New Testament, it’s even found in the Old Testament.

Consider Daniel 12:2: “And many of those who sleep in the dust of the earth shall awake, some to everlasting life, and some to shame and everlasting contempt.” This verse is not denying a disembodied afterlife between death and resurrection. Rather, it is affirming that the souls of the dead, whose bodies appear to be asleep in in the “dust of the earth,” shall be “awakened” and raised from the dead.

Notice that some are raised “to everlasting life,” but others to “everlasting contempt.” Cooper writes, “This verse . . . connects resurrection, judgment, and two eternal destinies.”{13} The Old Testament suggests that the souls of the dead will one day be reunited with their bodies for all eternity. As Moreland observes, “Old Testament teaching implies that the soul or spirit is added to flesh and bones to form a living human person (Genesis 2:7; Ezekiel 37) and that the resurrection of the dead involves the re-embodiment of the same soul or spirit (Isaiah 26:14, 19).”{14}

How might we sum up Old Testament teaching about the nature and destiny of human beings? First, human beings appear to be composed of both body and soul. When God created Adam, he first formed his body from the dust of the earth, and then “breathed into his nostrils the breath of life” (Genesis 2:7). This at least hints at the possibility that human beings are a body-soul composite. The evidence for this is strengthened, however, when we consider Old Testament teaching about life after death.

Throughout the Old Testament we see evidence for continued personal existence, after the death of the body, in a place called Sheol. An interesting example of this can be seen when Saul, with the help of a medium, calls up the prophet Samuel from the dead. We saw that Samuel continues to exist and retain his personal identity even after the death of his body (1 Samuel 28).

But this was not the end of the story. For the Old Testament also teaches that the souls of the dead will one day be reunited with resurrected bodies, either to enjoy eternal life on a new earth, or to suffer

eternal shame and contempt. This, in a nutshell, is what the Old Testament has to say about the nature and destiny of human beings.

Notes

1. John W. Cooper, Body, Soul & Life Everlasting: Biblical Anthropology and the Monism-Dualism Debate (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2000), Loc. 727-39, Kindle.

2. See the story in Genesis 35:16-20.

3. J. P. Moreland, The Soul: How We Know It’s Real and Why It Matters (Chicago: Moody, 2014), 45, Kindle.

4. The material in this paragraph is indebted to Moreland, The Soul, 45-46.

5. Cooper, Body, Soul & Life Everlasting, Loc. 810.

6. Cooper, Body, Soul & Life Everlasting, Loc. 783.

7. Moreland, The Soul, 51.

8. Moreland, The Soul, 52.

9. Cooper, Body, Soul & Life Everlasting, Loc. 906. The preceding words, concerning hope “beyond the grave” are also taken from Cooper, Loc. 902.

10. Hans Walter Wolff, Anthropology of the Old Testament, 109; cited in Cooper, Body, Soul & Life Everlasting, Loc. 912.

11. C.S. Lewis, Reflections on the Psalms (New York: Harcourt Brace & Company, 1986), 36.

12. Lewis, Reflections on the Psalms, 36-43.

13. Cooper, Body, Soul & Life Everlasting, Loc. 916.

14. Moreland, The Soul, 53.

©2022 Probe Ministries

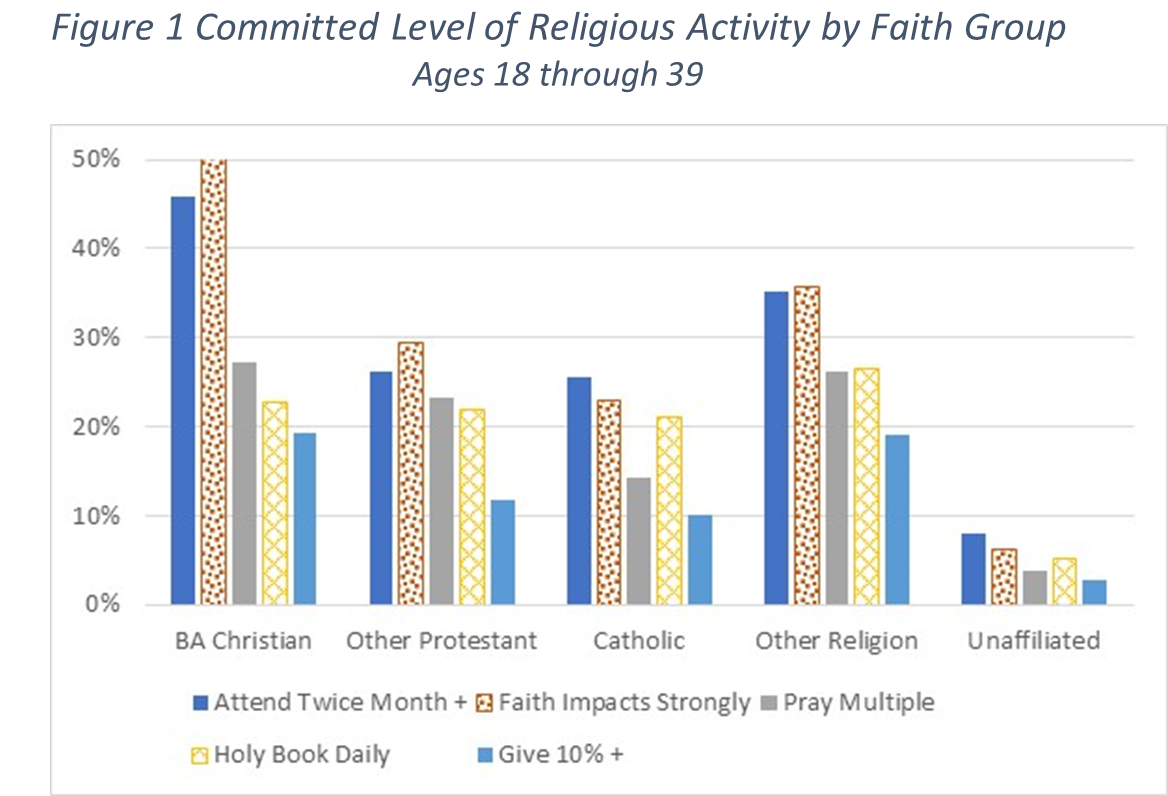

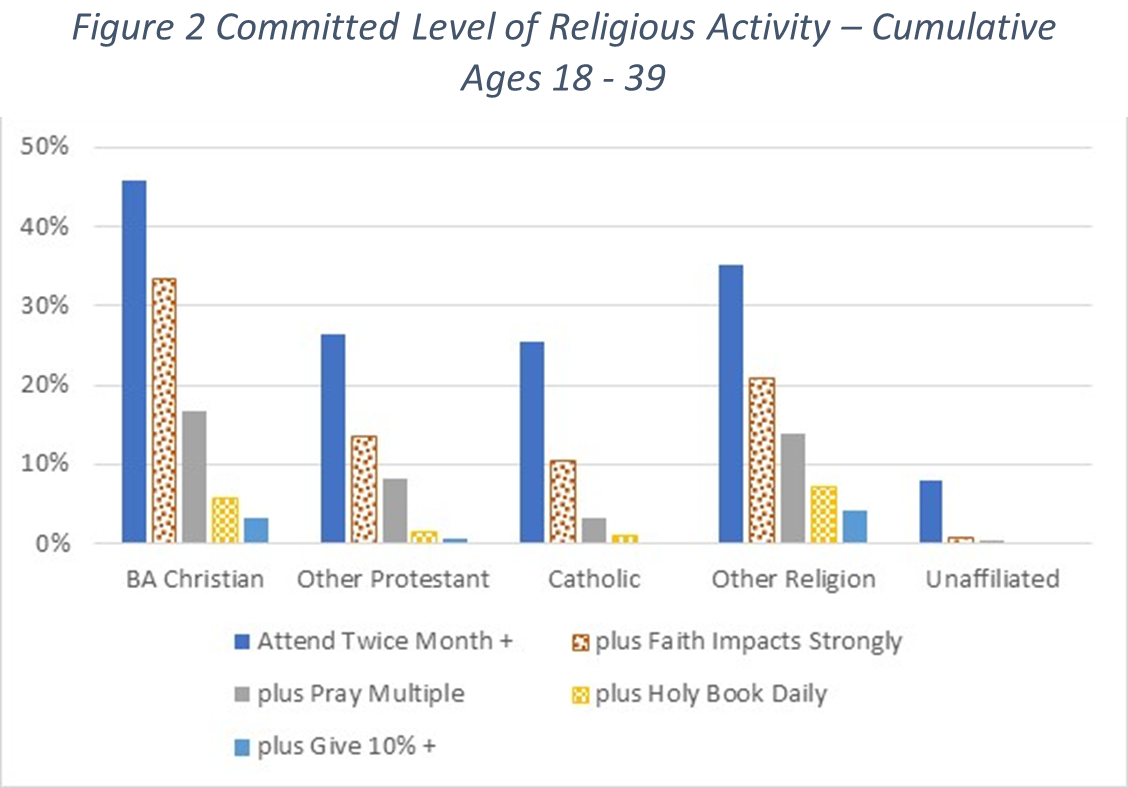

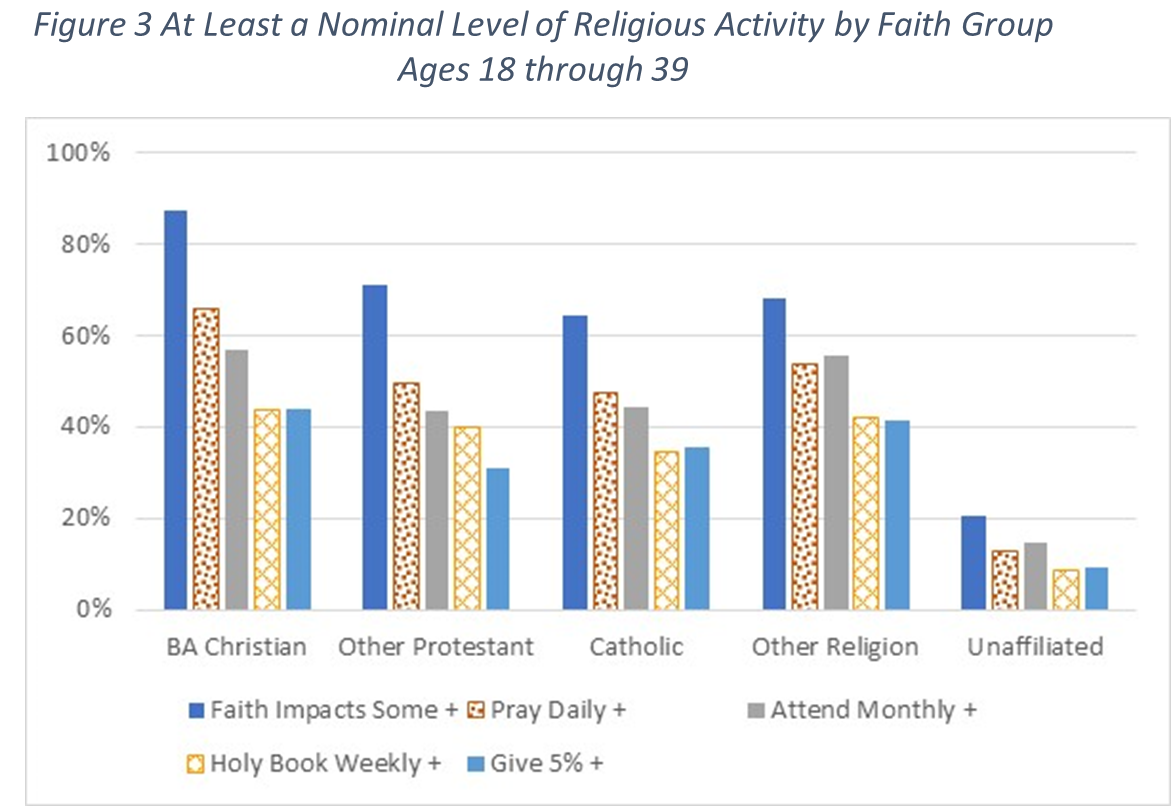

Nominal or Committed Levels of Religious Activity

Nominal or Committed Levels of Religious Activity

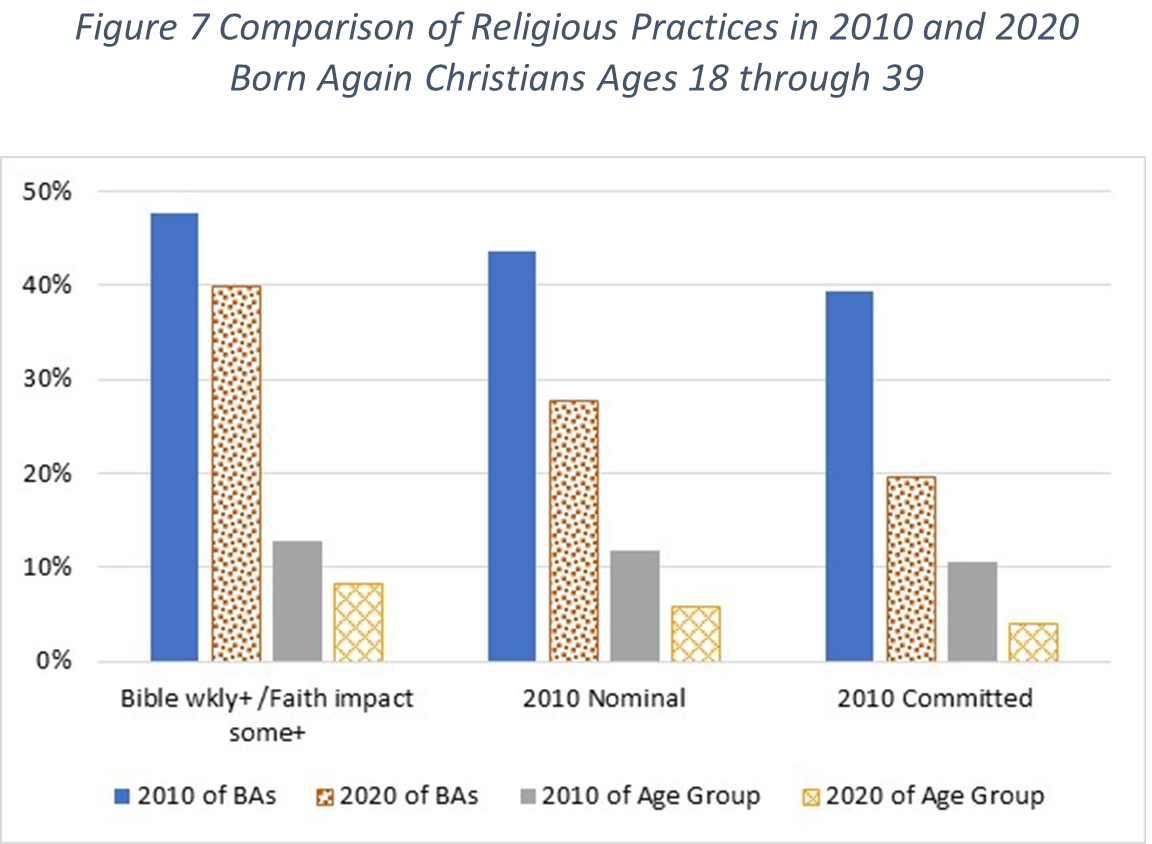

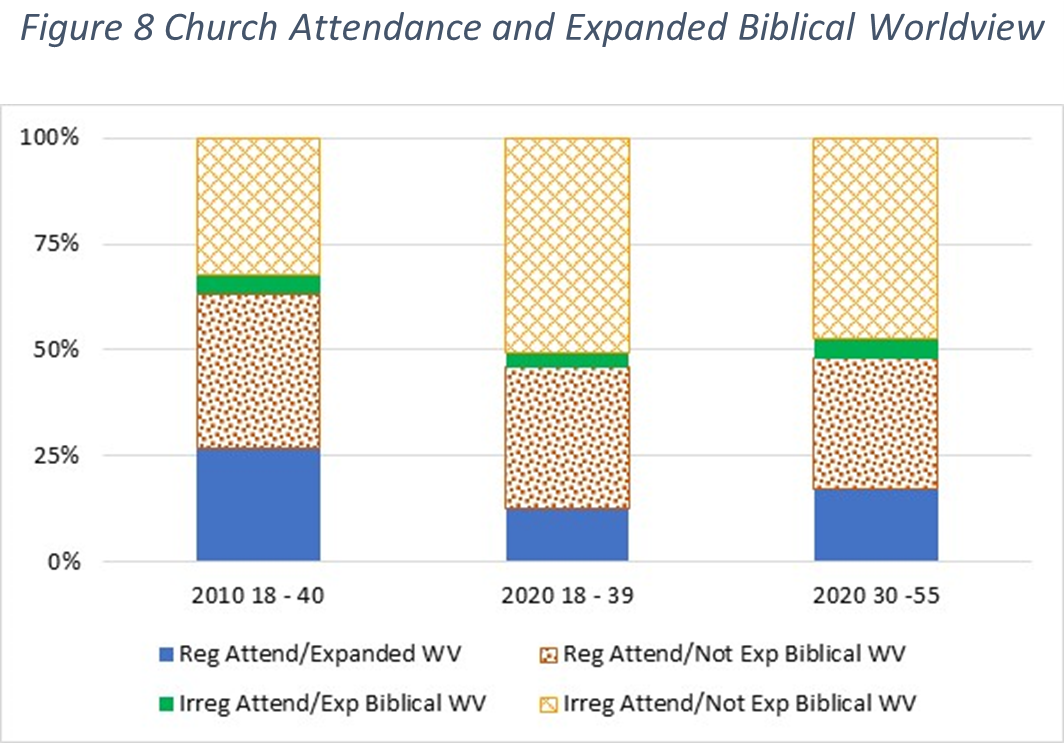

The figure on the left compares the findings from 2010 with those from 2020 using the more stringent Expanded Biblical Worldview. The values shown are the percent of Born-Again Christians (so all columns add up to 100% even though the percentage of Born Again Christians is less in 2020). Two age ranges are used in 2020; the first one is basically the same age range used in 2010 (18 – 39) and the second age range (30 – 55) is very close to the age range of the 2010 survey aged by the ten years that have gone by.

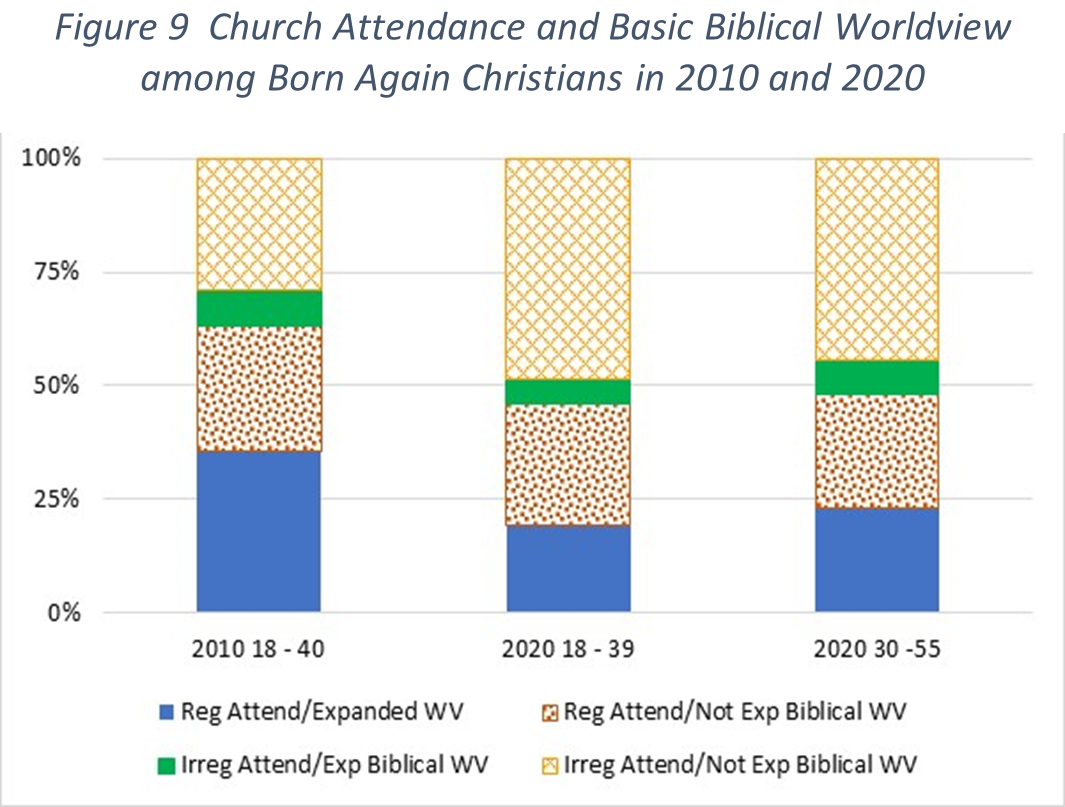

The figure on the left compares the findings from 2010 with those from 2020 using the more stringent Expanded Biblical Worldview. The values shown are the percent of Born-Again Christians (so all columns add up to 100% even though the percentage of Born Again Christians is less in 2020). Two age ranges are used in 2020; the first one is basically the same age range used in 2010 (18 – 39) and the second age range (30 – 55) is very close to the age range of the 2010 survey aged by the ten years that have gone by. Now let’s examine the same chart using a Basic Biblical Worldview. We see nearly the same features as discussed above. A significant drop is shown in those with regular attendance and a Basic Biblical Worldview coupled with a significant increase in those with irregular attendance and no Basic Biblical Worldview.

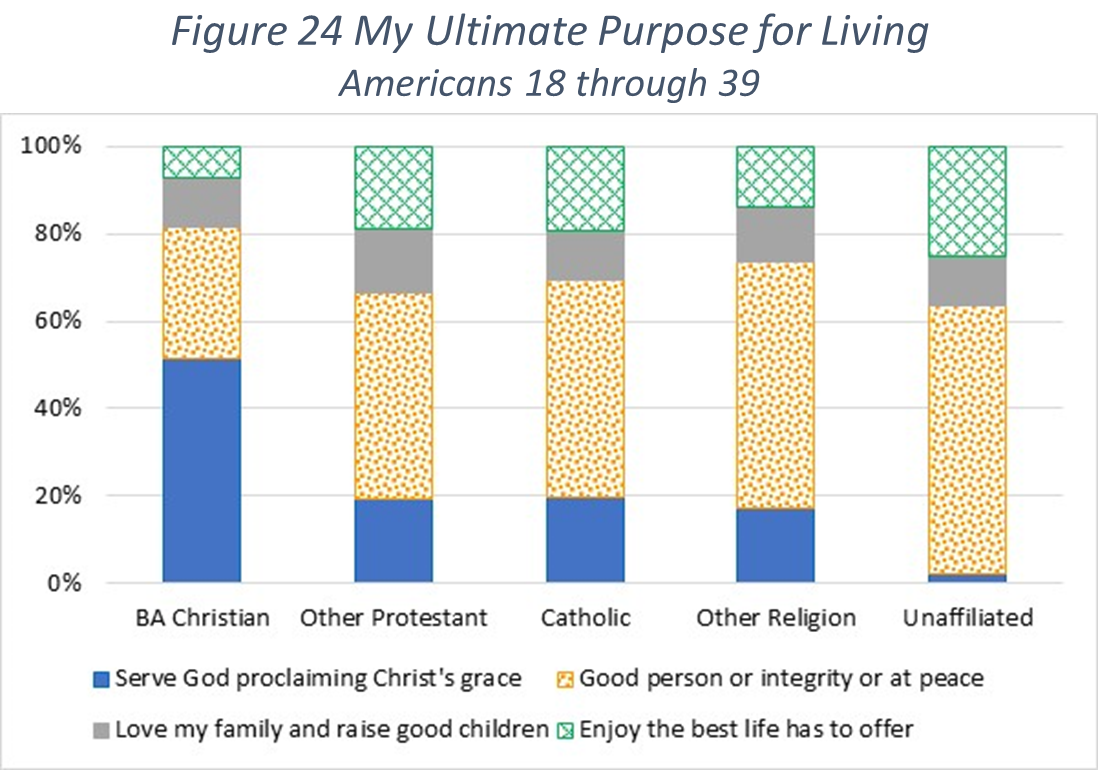

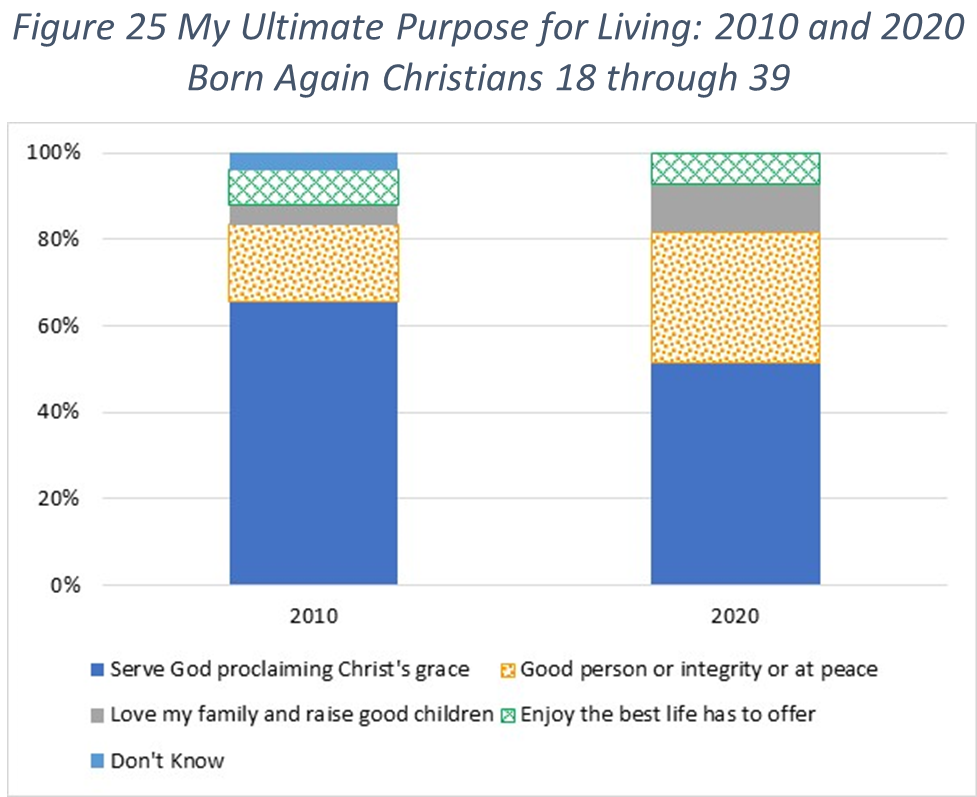

Now let’s examine the same chart using a Basic Biblical Worldview. We see nearly the same features as discussed above. A significant drop is shown in those with regular attendance and a Basic Biblical Worldview coupled with a significant increase in those with irregular attendance and no Basic Biblical Worldview. The results are charted in the graph to the left. As shown, just over half of Born Again Christians profess an eternal perspective. This means almost half do not, with most of those selecting a purpose that focuses on good behaviors in their personal life.

The results are charted in the graph to the left. As shown, just over half of Born Again Christians profess an eternal perspective. This means almost half do not, with most of those selecting a purpose that focuses on good behaviors in their personal life.

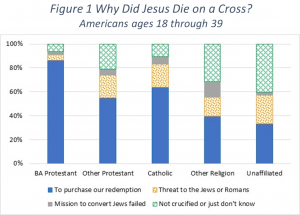

The responses for ages 18 through 39 are shown in Figure 1. As shown, Born Again Protestants have a far greater percentage, over 85%, stating that Jesus was crucified to purchase our redemption. One would suspect that all Protestant and Catholic leaders would want their people to know that Jesus’ death on the cross was for their redemption. Yet, less than two thirds of each group selected that answer. Note that the answer to this question did not say that salvation was through grace alone. So even those with a works-based gospel should still select that answer.

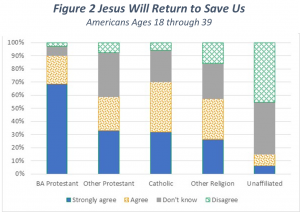

The responses for ages 18 through 39 are shown in Figure 1. As shown, Born Again Protestants have a far greater percentage, over 85%, stating that Jesus was crucified to purchase our redemption. One would suspect that all Protestant and Catholic leaders would want their people to know that Jesus’ death on the cross was for their redemption. Yet, less than two thirds of each group selected that answer. Note that the answer to this question did not say that salvation was through grace alone. So even those with a works-based gospel should still select that answer. The results for this question follow a similar pattern to those for the first question above with a little less surety shown among Christians. As shown, just over two thirds of Born Again Protestants strongly agree that Jesus will return to save. Meaning that almost one third of them are not absolutely sure of Jesus’ return.

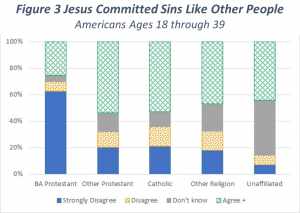

The results for this question follow a similar pattern to those for the first question above with a little less surety shown among Christians. As shown, just over two thirds of Born Again Protestants strongly agree that Jesus will return to save. Meaning that almost one third of them are not absolutely sure of Jesus’ return. Young adult American beliefs about this statement follow a similar pattern as the first two questions. Once again, about one third of Born Again Protestants either Don’t Know or Agree with this statement. Having this large a number of Born Again Protestants who don’t accept a primary belief of Biblical Christianity is disappointing.

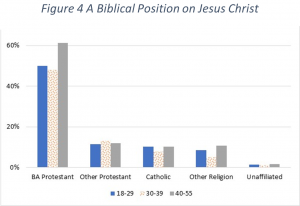

Young adult American beliefs about this statement follow a similar pattern as the first two questions. Once again, about one third of Born Again Protestants either Don’t Know or Agree with this statement. Having this large a number of Born Again Protestants who don’t accept a primary belief of Biblical Christianity is disappointing. What happens when we look at how many Born Again Protestants take a biblically consistent view on all three of these questions? Consider the results shown in Figure 4. First, we see that young adult Born Again Protestants drop from about two thirds for the individual questions down to about one half when looking at all three questions. It appears that about one half of those categorized as Born Again Protestants are trusting Jesus to save them but do not have a good understanding of biblical teaching on Jesus.

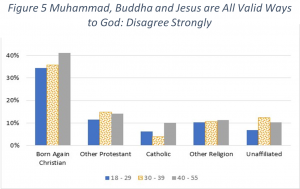

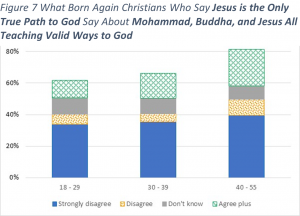

What happens when we look at how many Born Again Protestants take a biblically consistent view on all three of these questions? Consider the results shown in Figure 4. First, we see that young adult Born Again Protestants drop from about two thirds for the individual questions down to about one half when looking at all three questions. It appears that about one half of those categorized as Born Again Protestants are trusting Jesus to save them but do not have a good understanding of biblical teaching on Jesus. First let’s look at just question number one across the various religious groups, looking for the answer Disagree strongly as shown in Figure 5

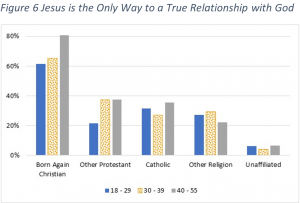

First let’s look at just question number one across the various religious groups, looking for the answer Disagree strongly as shown in Figure 5 Instead, we asked this second question in a slightly different way but with the same intent: “I believe that the only way to a true relationship with God is through Jesus Christ.” We thought that this question would be

Instead, we asked this second question in a slightly different way but with the same intent: “I believe that the only way to a true relationship with God is through Jesus Christ.” We thought that this question would be However, the survey respondents show us that one does not have to give answers which logically support one another. Even if some of the respondents misread the statement, the difference between the two is great enough that it is safe to assume that the results are not primarily attributable to misreading.

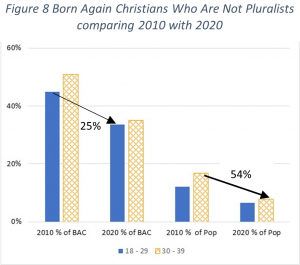

However, the survey respondents show us that one does not have to give answers which logically support one another. Even if some of the respondents misread the statement, the difference between the two is great enough that it is safe to assume that the results are not primarily attributable to misreading. How have the statistics on Born Again Christians and pluralism changed from 2010 to 2020? As shown in the figure, we see a significant drop in the percent of BACs who are not pluralists. Those age 18 to 29 drop by 25% (from 45% to 34% of all BACs) and those age 30 to 39 drop by 31% (from 51% to 35% of all BACs).

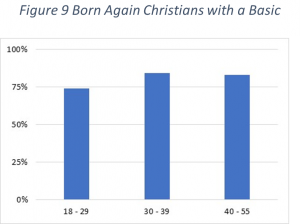

How have the statistics on Born Again Christians and pluralism changed from 2010 to 2020? As shown in the figure, we see a significant drop in the percent of BACs who are not pluralists. Those age 18 to 29 drop by 25% (from 45% to 34% of all BACs) and those age 30 to 39 drop by 31% (from 51% to 35% of all BACs). What about that smaller subset of people who have a Basic Biblical Worldview? Do a majority of them also have a pluralistic worldview? The answer is no. As shown, between 75% and 85% of them are not pluralists.

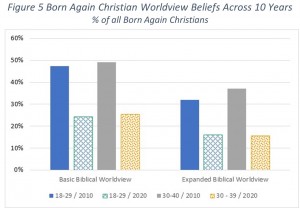

What about that smaller subset of people who have a Basic Biblical Worldview? Do a majority of them also have a pluralistic worldview? The answer is no. As shown, between 75% and 85% of them are not pluralists. Now let’s compare these 2020 results with the results from our 2010 survey. Figure 5 shows the results across this decade for Born Again Christians looking at the percent who agree with the worldview answers above. As shown, there has been a dramatic drop in both the Basic Biblical Worldview and the Expanded Biblical Worldview.

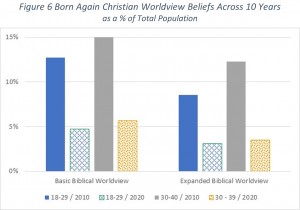

Now let’s compare these 2020 results with the results from our 2010 survey. Figure 5 shows the results across this decade for Born Again Christians looking at the percent who agree with the worldview answers above. As shown, there has been a dramatic drop in both the Basic Biblical Worldview and the Expanded Biblical Worldview. However, because the percent of the population who profess to being born again has dropped over the last ten years as well, the situation is even worse. We need to look at the percent of Americans of a particular age range who hold to a Biblical Worldview. Those results are shown in Figure 6. Once again, comparing the 18–29 age group from 2010 with the same age group ten years later now 30–39, we find an even greater drop off. For the Basic Biblical Worldview, we see a drop off from 13% of the population down to 6%. For the Expanded Biblical Worldview, the decline is from 9% down to just over 3% (a drop off of two thirds).

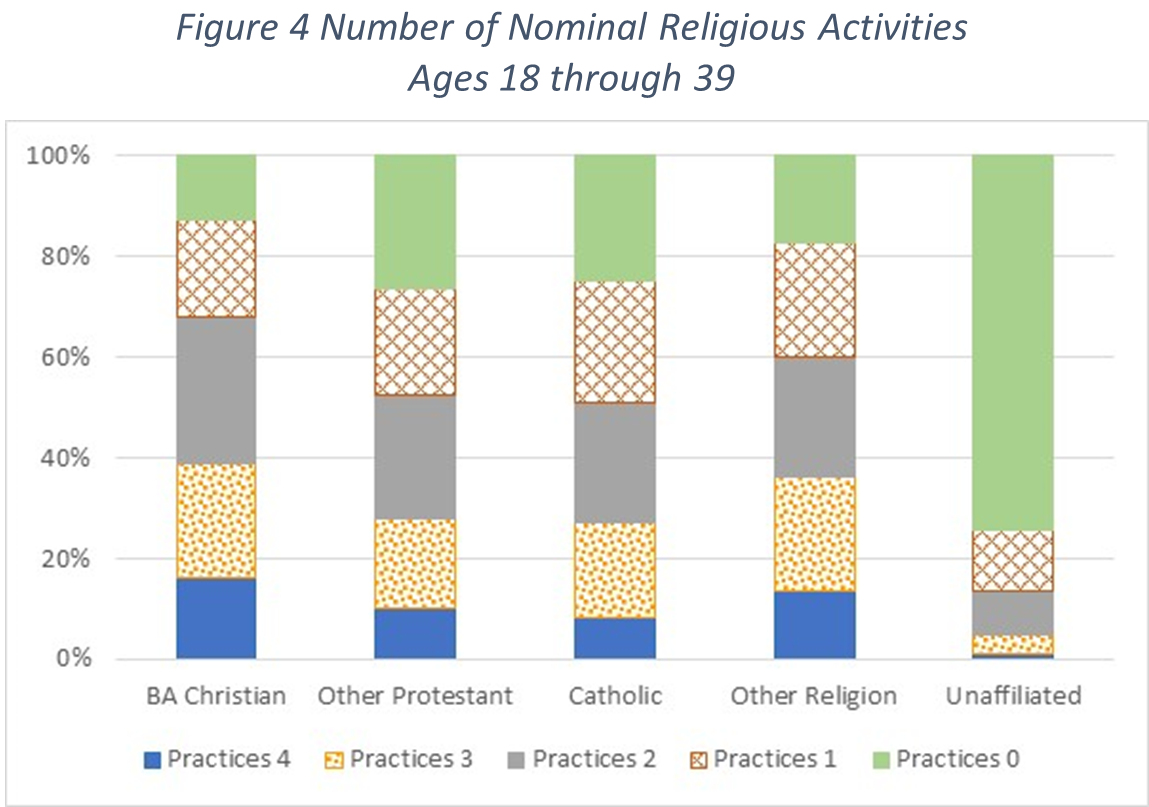

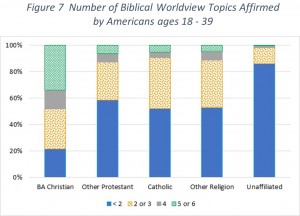

However, because the percent of the population who profess to being born again has dropped over the last ten years as well, the situation is even worse. We need to look at the percent of Americans of a particular age range who hold to a Biblical Worldview. Those results are shown in Figure 6. Once again, comparing the 18–29 age group from 2010 with the same age group ten years later now 30–39, we find an even greater drop off. For the Basic Biblical Worldview, we see a drop off from 13% of the population down to 6%. For the Expanded Biblical Worldview, the decline is from 9% down to just over 3% (a drop off of two thirds). Rather than look at the two biblical worldview levels discussed above, we will look at how many of the six biblical worldview questions they answered were consistent with a biblical worldview. In the chart, we look at 18- to 39-year-old individuals grouped by religious affiliation and map what portion answered less than two of the questions biblically, two or three, four, or more than four (i.e., five or six).

Rather than look at the two biblical worldview levels discussed above, we will look at how many of the six biblical worldview questions they answered were consistent with a biblical worldview. In the chart, we look at 18- to 39-year-old individuals grouped by religious affiliation and map what portion answered less than two of the questions biblically, two or three, four, or more than four (i.e., five or six).