Rick Wade distills an in-depth e-mail dialog with an atheist in which he addresses her doubts and arguments concerning the existence of God.

This article is also available in Spanish.

This article is also available in Spanish.

About Our Dialogue

The Conversation Begins

In the fall of 1999 I became involved in an e-mail conversation with an atheist who wrote in response to a program I’d written titled The Relevance of Christianity. In this program [Ed. note: The transcripts for our radio programs become the online articles such as the one you are reading.] I contrast Christianity and naturalism on the matters of meaning, morality, and hope.{1} She wrote to say that she was able to find these things in her own philosophy of life without God. If such things can be had without God, why bother bringing Him in, especially given all the trouble religion causes?

Stephanie has an undergraduate degree in philosophy, and is pursuing her doctorate in physics.{2} Our conversation has been quite cordial, and in our over two-month long conversation I’ve grown to respect her. She isn’t just out to pick a fight. I try to keep in mind that, if her ideas seem grating on me, mine are just as grating on her.

Stephanie seems genuinely baffled by theistic belief. If God is there, He is outside the bounds of what we can know. While someone like Kierkegaard saw good reason to take a “leap of faith” into that which can’t be proved, she sees no reason to do that. “I think that if I had faith it would be like his,” she says, “but the leap seems, at this point, both futile and risky.”

Stephanie has three general objections to belief in God. First, she believes that the evidence is insufficient. The evidence of nature is all she has, and God is said to have attributes beyond the natural. There’s no way to know about such things. Second, she believes that theistic belief adds nothing of importance to our lives or to what we can know through science. I asked her, “What is it about Christianity that turns you off to it?” And she replied, “I imagine believing, and I am no more fulfilled and no less worried than I am when I am not believing. God just does not seem to be a useful, beneficial, or tenable idea.” Third, she believes that religion is morally bad for people. It grounds morality in fear, she believes, and it produces a dogmatism in adherents that prompts such behavior as killing abortion providers.

Stephanie began our correspondence not to be given proofs for the existence of God, but for me “to explain more personally His relevance.” What is called for, then, is defense and explication rather than persuasion.

Basic Elements of Stephanie’s Atheism

There are three main elements underlying Stephanie’s atheism. The first is reason, which she believes is sufficient for understanding our world, for morality, and for understanding and cultivating human qualities such as “aesthetic appreciation, compassion, and love.” It is, of course, the final authority on religion as well. Reason does not admit faith. Insofar as one has admitted faith into the equation, one has moved toward irrationalism. As George Smith wrote, “I will not accept the existence of God, or any doctrine, on faith because I reject faith as a valid cognitive procedure. . . . If theistic doctrines must be accepted on faith, theism is necessarily excluded.”{3}

The second element, nature, is reason’s best source for information. Stephanie says, “I have no access to anything outside of the natural universe and my own mind.”

The package is complete with Stephanie’s commitment to science, which is the tool reason uses to understand nature. It alone is capable of giving us “objective, investigable knowledge,” she says. In fact, I think it is fair to label Stephanie’s approach to knowledge “scientistic.” There seems to be no area of life which need not be submitted to science to be considered rational, and for which scientific investigation isn’t sufficient.

The reason/nature/science triumvirate provides the structure for acquiring knowledge. To go beyond it is to move into irrationalism, Stephanie believes. There’s certainly no reason to add God. She says, “As I understand it, the idea of God as a creator or guarantor adds nothing but unjustified mysticism to my knowledge.”{4}

Theists have no problem with using reason to understand our world, or with the study of nature, or with using the tools of science. The problem comes when Stephanie concludes that nothing can be known beyond nature analyzed scientifically. She believes that nature is all that is there or at least all that is knowable. Stephanie says she doesn’t consciously start with naturalism; she has no desire to “champion naturalism as a dogma,” she says. However, since science “only permits investigation of natural, repeatable phenomena,” and she is satisfied with that, her view is restricted to the scope of nature. She even goes so far as to say, “I equate rationality and naturalism.”

It seems, then, that the deck is stacked from the beginning. Stephanie’s emphasis on science doesn’t necessarily prevent her from finding God, but her naturalism does.

Insufficient Evidences

The Evidentialist Objection

Let’s look at Stephanie’s three basic objections to theistic belief, beginning with the charge that there is insufficient evidence to believe. Rather than offer a defense for theistic belief, let’s look at the objection itself.

Stephanie’s argument is called the “evidentialist objection.” She quotes W. K. Clifford, a 19th century scholar who wrote, “It is wrong always, everywhere, and for everyone, to believe anything upon insufficient evidence.”{5} Stephanie’s objection is that there isn’t enough evidence to believe in God. The first question, of course, is what constitutes good evidence. Another question is whether we should accept Clifford’s maxim in the first place.

Some atheists believe they don’t bear the same burden of adducing evidences for their beliefs as theists do. They say atheism is the “default” position. To believe in God is to add a belief; to not add that belief is to remain in atheism or perhaps agnosticism.{6} But atheism isn’t a “zero belief” system. Western atheism is typically naturalistic. Atheists hold definite views about the nature of the universe; there’s no reason to think that atheism is where we all automatically begin in our thinking, such that to move to theism is to add a belief while to not believe in God is to remain in atheism. It’s hard not to agree with Alvin Plantinga that the presumption of atheism “looks like a piece of merely arbitrary intellectual imperialism.”{7} If theists have to give evidences, so do atheists.

Stephanie, however, doesn’t defend her atheism or naturalism this way. She believes that reason using the tools of science is the only reliable means of attaining knowledge. The result of her observations, she says, is naturalism. There simply aren’t sufficient evidences for believing in God, at least the kinds of evidences that are trustworthy. Which kind are trustworthy? Stephanie wants evidences in nature, because in nature one finds “objective, investigable knowledge.” However, she doesn’t believe evidences for God can be found there. God must be outside of nature if He exists. She said, “You may rightly ask what kind of naturalistic evidence I would ever accept for God, and I would have to answer, none.’ Because once a naturalistic investigation turns to God with its hands up, it ceases to be naturalistic, and so it ceases to refer to anything that I can hope to investigate. I lack a sense for God and I have no access to anything outside of the natural universe and my own mind.” She said in a later letter that the cause of the universe may have had an agent. But when we begin adding other attributes to this agent, attributes which can’t be studied scientifically, we get into trouble. “As soon as you talk about God as having infinite attributes, those attributes actually begin to lose meaning,” she says. “My view,” she says, “is that it’s just as well to call the unknown cause what it is–an unknown cause–until the means to investigate it are developed.” And by this she means natural means. A Naturalistic Twist

The first problem here is obvious: Stephanie has biased the argument in her favor by her restrictions on knowledge to the realm of nature. She reduces our resources for knowledge to the scientifically verifiable. Such reductionism is arbitrary. By reducing all knowledge to that which can be discovered scientifically, Stephanie has cut out significant portions of our knowledge. Philosopher Huston Smith said this: “It is as if the scientist were inside a large plastic balloon; he can shine his torch anywhere on the balloon’s interior but cannot climb outside the balloon to view it as a whole, see where it is situated, or determine why it was fabricated.”{8} Science can’t tell us what the final cause (or purpose or goal) of a thing is; in fact it can’t tell whether there are ultimate purposes. It cannot determine ultimate or existential meaning. While it can describe the artist’s paintbrush and pigments and canvas, it can’t measure beauty. Clifford’s Folly

Beyond this difficulty is the fact that Clifford’s maxim itself has problems.

First, the evidentialist approach is unreasonably restrictive. If we have to be able construct an argument for everything we believe¾and upon which we act–we will believe little and act little.

Second, this approach might have validity in science, but it leaves out other significant kinds of beliefs. Kelly Clark lists perceptual beliefs, memory beliefs, belief in other minds, and truths of logic as other kinds of “properly basic” beliefs that we hold without inferring them from other beliefs.{9} Beliefs involved in personal relationships are another example. Relationships often require a willingness to believe in a friend apart from sufficient evidences. In fact, the willingness to do so can have a positive effect on developing a good relationship. Beliefs about persons are still another example. I accept without proof that my wife is a person, that she isn’t an automaton, that she has intrinsic value, etc. These kinds of beliefs don’t require amassing evidences to formulate an inductive or deductive proof. Clifford’s maxim works well in scientific study, but not for beliefs about persons.

More to the point, religious beliefs don’t fit so neatly within evidentialist restrictions. They are more like relational beliefs since, in confronting a Supreme Being, one is not confronting a hypothesis but a Person.

Fourth, Stephanie’s use of Clifford’s evidentialism is biased in her favor because, as we discussed above, her satisfaction with the deliverances of scientific investigation means she will only accept evidences in the natural order. Do We Have Good Reasons for Believing?

Some Christian scholars are saying that we don’t have to have evidences for belief, meaning that we don’t have to be able to put together an argument whereby God’s existence is inferred from other beliefs. Our direct experience of God is sufficient for rational belief (using “experience” in a broader sense than emotional experience).{10} Belief in God is therefore properly basic.

This is not to say there are no grounds for believing, however. Drawing from John Calvin, Alvin Plantinga says that we have an ingrained tendency to recognize God under appropriate circumstances. Of course, there are a number of reasons or grounds for believing. These include direct experience of God, the testimony of a people who claim to have known God, written revelation which makes sense (if one is open to the supernatural), philosophical and scientific corroboration, the historical reality of a man named Jesus who fulfilled prophecies and did miracles, etc. Am I reversing myself here? Do we need reasons or not? The point is this: while there are valid reasons for believing in God, what we do not need to do is submit our belief in God ultimately to Clifford’s maxim, especially a version of it already committed to naturalism. We can recognize God in our experience, and this belief can be confirmed by various reasons or evidences. Rather than view our belief as guilty until proven innocent, as the evidentialist objection would have it, we can view it as innocent until proven guilty. Let the atheists prove we’re wrong.

Theism Adds Nothing

The second general objection to belief in God Stephanie offers is that it adds nothing of value to life and to what we can know by reason alone. Is this true? Meaning

Consider the subject of meaning. Stephanie said she finds meaning in the everyday affairs of life without worrying about God. Let me quote an extended passage from Stephanie’s first letter on the subject of meaning. Her reference in the first line is to a quotation from a book by Albert Camus.

Your quote from The Stranger (“I laid my heart open to the benign indifference of the universe”) expresses well a feeling that I have had often. The universe is not concerned with me, so I do not need to bow and cater to anything in it; I can merely be grateful (yes, actually grateful to nothing in particular) that I can walk along a path with trees and breathe in the crisp late autumn, that I can watch cotton motes fly into my face, facing the sun, that I can struggle and wrangle my way into knowing that Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle is that which keeps atoms from collapsing (in nanoseconds!!). I find meaning in my relationship with my parents, brothers, and in my marriage; my husband is the most kind, capable, ethical, and wise person I’ve ever met. These things are sufficiently meaningful for me; I do not think that true meaning is necessarily eternal and I do not demand recognition from the universe or the human notion of its maker. I am convinced that belief in a personal god could do nothing but dilute these things by subordinating them to something as slippery as God.

Thus, Stephanie believes that God isn’t necessary for her to find meaning in life.

I replied that her naturalism provides no meaning beyond what we impose on the universe. We can pretend there is purpose behind it all, but a universe that doesn’t care about us doesn’t care about our superimposed meanings either. What does she do when the meaning she has given the universe doesn’t find support in the universe itself? I wrote:

You might see this earth as a beautiful ‘mother’ of sorts which nourishes and sustains its inhabitants. Do people who suffer through hurricanes or earthquakes or tornadoes see it as such? Do people who live in almost lifeless deserts who have to spend their days walking many miles to get water and who struggle to eke out a meager existence from the land find beauty and meaning in it? Often people who live close to the land do indeed find a special meaning in nature itself, but by and large they also believe there is a higher power behind it who not only gives meaning to the universe but who gives meaning to the struggle to survive and to the effort to preserve nature.

When I said that all her efforts at accomplishing some good could come to naught, and thus be ultimately meaningless, her response was, “That’s OK. . . . I’m not looking for universal or eternal meaning.”

It’s hard to know what to say to that. We might follow Francis Schaeffer’s advice and “take the roof off;”{11} in other words, expose the implications of her beliefs. Stephanie says she isn’t a nihilist (one who believes that everything is thoroughly meaningless and without value); perhaps she could be called an “optimistic humanist” to use J. P. Moreland’s term.{12} She believes there are no ultimate values; rather, we give life whatever meaning we choose. However, this position has no rational edge on nihilism. It simply reflects a decision to act as if there is meaning. Such groundless optimism is no more rationally justifiable than nihilism. It is just intellectual make-believe designed to help us be content with our lot¾adult versions of children’s fairy tales.

Since the loss of absolute or transcendent meaning undercuts all absolute value, each person must choose his or her own values, moral and otherwise. As I told Stephanie, others might not agree with her values. The Nazis thought there was valid meaning in purifying the race. What did the Jews think?

What can be seen as meaningful for the moment is just that–meaningful for the moment. Death comes and everything that has gone before it comes to nothing, at least for the individual. Sure, one can find meaning in, say, working to discover a cure for a terrible disease knowing that it will benefit countless people for ages to come. But those people who benefit from it will die one day, too. And in the end, if atheists are correct, the whole race will die out and all that it has accomplished will come to naught.{13} Thus, while there may be temporal significance to what we do, there is no ultimate significance. Can the atheist really live with this?

By contrast, the eternal nature of God gives meaning beyond the temporal. What we do has eternal significance because it is done in the context of the creation of the eternal God who acts with purpose and does nothing capriciously. More specifically, belief in God locates our actions in the context of the building of His kingdom. There is a specific end toward which we are working that gives meaning to the specific things we do.

Strictly speaking, then, we might agree with Stephanie that it’s true God doesn’t add anything. Rather, He is the very ground of meaning. Morality

What about morality? Although Stephanie says that naturalistic morality is superior, when pressed to offer a standard she was only able to offer a basic impulse to kindness. In addition, she said, “I think that it is sufficient to have an internal sense of the golden rule, and I think that’s a natural development.” She used the metaphor of a child growing up to illustrate our growth in morality. Reason is all that is needed for good moral behavior. If biblical moral principles agree with reason they are unnecessary. If they don’t, “they are absurd.”

In response I noted that we can measure the growth of a child by looking at an adult; the adult we might call the telos or goal of the child. We know what the child is supposed to become. What is the goal or end, in her view, of morality? What is the standard of goodness to which we should attain? Stephanie accepts the golden rule but can give me no reason why I should. Reason by itself doesn’t direct me to. The golden rule assumes a basic equality between us all. Where does this idea come from? Even if it is employed only to safeguard the survival of the race, by what standard shall we say that’s a good thing? Maybe we need to get out of the way for something else.

God, however, provides a standard grounded in His character and will to which we all are subject. He doesn’t change on fundamental issues (although God has pressed certain moral demands on His people more at one time than another in keeping with the progress of revelation{14}), and His law is suited to our nature and our needs. The universe doesn’t necessarily stand behind Stephanie’s chosen morality, but God–and the universe¾stand behind His.

One final note. Showing the weaknesses of naturalism with respect to morality is not to say that all atheists are evil people. In her first letter, Stephanie wrote, “I take offense at your statement that the relativism of a godless morality permits things like the destruction of the weak and the development of a master race.’ . . . I find this charge of atheist amorality from Christians to be horribly persistent and unfair.” I noted that I never said in the Relevance radio program that all atheists are immoral or amoral. What I said was that “atheism itself makes no provision for fixed moral standards.” I asked Stephanie to show me what kind of moral standard naturalism offers. In fact, it offers none. As I noted earlier, Stephanie doesn’t want to “champion naturalism.” She knows it has nothing to offer. In fact, in one of her latest posts, she admitted that her philosophy only leaves her with “a frail pragmatism” and even “a certain moral relativism” because she doesn’t have “the absolute word of God to fall back upon.” She only has her own moral standards that have no hold on anyone else. Until she can show me what universal standard naturalism offers, I’ll stand behind what I said about what naturalism allows. Hope

Let’s turn our attention now to hope. Stephanie says that when she dies she will cease to exist. She thus has to be satisfied with the here and now. If there is nothing else, one must make do. Stephanie said, “I am satisfied with the time that I have here and now to think and feel and explore. You say, ‘an impersonal universe offers no rewards,’ but I am simply unable to comprehend the appeal of the vagaries of the Christian Heaven, especially with the heavy toll that they seem to of necessity take on intellectual honesty. If your notion of true hope requires a belief that one is promised eternal glory and fulfillment, then I cannot claim it. I am unable to comprehend what that could mean.” Maybe the reason she is unable to comprehend it is her scientistic approach. Heaven isn’t something one can analyze scientifically. P>In response I noted that she stands apart from the majority of people worldwide. There is something in us that yearns for immortality, I said. Of course, the various religions of the world have different ways of defining what the eternal state is and how to attain it. Christians believe we were created to desire it; it is a part of our make-up because we were created by an immortal God to live forever. If naturalism is true, I asked, how do you explain the desire for immortality?

If we had no good reason to believe in “the vagaries of the Christian Heaven,” I suppose it would be foolish to allow it to govern one’s life. However, we do have good reasons: the promise of God who doesn’t lie, and the resurrection of Jesus. We also have the witness of “eternity set in our hearts.” (Eccles. 3:11) Because of this hope–which isn’t a “cross your fingers” kind of hope, but is justified confidence in the future–our labors here for Christ’s kingdom will not die with us, but will have eternal significance. They are what is called “fruit that remains” (John 15:16), or the work which is “revealed with fire.” (1 Cor. 3:13-14) Science

We’re still thinking about what belief in God adds to our lives and our knowledge. One area in which even some theists don’t want to bring God is science itself. Does theistic belief add anything to science, or is its admission a source of trouble?

Much ink has been spilled over this question. Aside from naturalistic evolutionists, some theistic scientists believe that to go beyond what is called “methodological naturalism” is risky.{15} That’s the belief that, for the purposes of scientific investigation, the scientist should not fall back on God as an explanation, but should stay within the bounds of that which science can investigate. However, not everyone is of this opinion. As scholars active in the intelligent design movement are showing today, it isn’t necessarily so that the supernatural has no place in science.

William Dembski, a leader in the intelligent design movement, says that, far from harming scientific inquiry, design adds to scientific discovery. For one thing, it fosters inquiry where a naturalistic view might see no need. Dembski names the issues of “junk DNA” and vestigial organs as examples. Is this DNA really “junk”? Did these vestigial organs have a purpose or do they have a purpose still? Openness to design also raises a new set of research questions. He says, “We will want to know how it was produced, to what extent the design is optimal, and what is its purpose.” Finally, Dembski says, “An object that is designed functions within certain constraints.” So, for example, “If humans are in fact designed, then we can expect psychosocial constraints to be hardwired into us. Transgress those constraints, and we as well as our society will suffer.”{16}

In sum it simply isn’t true that belief in God adds nothing of value to our lives and our knowledge. After all, whereas Stephanie is restricted to explanations arising from the natural order, we have the supernatural order in addition.

Moral Problems with Theism

It Doesn’t Live up to Its Promises

A third general objection Stephanie has to theistic belief has to do with moral issues. Atheists say there are moral factors that count against believing in God. To show a contradiction between what the Bible teaches about God’s character and what He actually does is to show either that He really doesn’t exist or that He isn’t worthy of our trust.

One argument says that the Bible doesn’t live up to its promises. Stephanie pointed to the matter of unanswered prayer. She referred to a man who claimed to have been an evangelical who lost his faith primarily because of “the inefficacy of prayer.” She has concluded that “hoping at God gives you the same results’ that hoping at the indifferent universe does–none that are consistent enough to be useful!”

In response, I noted first that people often put God to the test as if He is the one who has to prove Himself. Do we have the right to expect Him to answer our prayers 1) just because we pray them, or 2) when we haven’t done what He has called us to do? People can’t live the way they want to and then expect God to 1jump when they pray. Second, God has promised His people that He will hear them and answer, but He doesn’t always answer prayers the way we expect or when we expect. Answers might be a long time coming, or they might come in totally unexpected ways. Or it might be that over time our understanding of the situation or of God’s desires changes so that we realize that we need to pray differently. Evil

The problem of evil is a significant moral issue in the atheist’s arsenal. We talk about a God of goodness, but what we see around us is suffering, and a lot of it apparently unjustifiable. Stephanie said, “Disbelief in a personal, loving God as an explanation of the way the world works is reasonable–especially when one considers natural disasters that can’t be blamed on free will and sin.”{17}

One response to the problem of evil is that God sees our freedom to choose as a higher value than protecting people from harm; this is the freewill defense. Stephanie said, however, that natural disasters can’t be blamed on free will and sin. What about this? Is it true that natural disasters can’t be blamed on sin? I replied that they did come into existence because of sin (Genesis 3). We’re told in Romans 8 that creation will one day “be set free from its slavery to corruption,” that it “groans and suffers the pains of childbirth together until now.” The Fall caused the problem, and, in the consummation of the ages, the problem will be fixed.

Second, I noted that on a naturalistic basis, it’s hard to even know what evil is. But the reality of God explains it. As theologian Henri Blocher said,

The sense of evil requires the God of the Bible. In a novel by Joseph Heller, “While rejecting belief in God, the characters in the story find themselves compelled to postulate his existence in order to have an adequate object for their moral indignation.” . . . When you raise this standard objection against God, to whom do you say it, other than this God? Without this God who is sovereign and good, what is the rationale of our complaints? Can we even tell what is evil? Perhaps the late John Lennon understood: “God is a concept by which we measure our pain,” he sang. Might we be coming to the point where the sense of evil is a proof of the existence of God?{18}

So, while it’s true that no one (in my opinion) has really nailed down an answer to the problem of evil, if there is no God, there really is no problem of evil. Does the atheist ever find herself shaking her fist at the sky after some catastrophe and demanding an explanation? If there is no God, no one is listening.

Biblical Morality

Moral Character of God

Another direction atheistic objections run with respect to moral issues is in regard to the character of God. Is He good like the Bible says?

The “Old Testament God” is a favorite target of atheists for His supposed mean spirited and angry behavior, including stoning people for picking up sticks on Sunday, and having prophets call down bears on children.{19} The story of Abraham and Isaac is Stephanie’s favorite biblical enigma. She asked if I would take a knife to my son’s throat if God told me to. Clearly such a God isn’t worthy of being called good.

Let’s look more closely at the story of Abraham. Remember first of all that God did not let Abraham kill Isaac. The text says clearly that this was a test; God knew that He was going to stop Abraham.

But why such a difficult test? Consider Abraham’s cultural background. As one scholar noted, “It must be ever remembered that God accommodates His instructions to the moral and spiritual standards of the people at any given time.”{20} In Abraham’s day, people offered their children as sacrifices to their gods. While the idea of losing his promised son must have shaken him deeply, the idea of sacrificing him wouldn’t have been as unthinkable to him as to us. Think of an equivalent today, something God might call us to do that would stretch us almost to the breaking point. Whatever we think of might not have been an adequate test for Abraham. God needed to go to the extreme with Abraham and command him to do something very difficult that wasn’t beyond his imagination given his cultural setting.

Next, notice that Abraham said to the men with him “we will worship and return to you.” (Gen. 22:5) The book of Hebrews explains that “He considered that God is able to raise people even from the dead, from which he also received [Isaac] back as a type” (11:17-19). Abraham believed what God had told him about building a great nation through Isaac. So, if Isaac died by God’s command, God would raise him from the dead.

Stephanie also objected to stories that told how God commanded the complete destruction of a town by the Israelites. The only way to understand this is to put it in the context of the nature of God and His opinion of sin, and the character of the people in question. God is absolutely holy, and He is a God of justice as well as mercy. To be true to His nature, He must deal with sin. Read too about the people He had the Israelites destroy. They were evil people. God drove them out because of their wickedness (Deut. 9:5). Walter Kaiser explains why the Canaanites were dealt with so severely.

They were cut off to prevent Israel and the rest of the world from being corrupted (Deut. 20:16-18). When a people starts to burn their children in honor of their gods (Lev. 18:21), practice sodomy, bestiality, and all sorts of loathsome vices (Lev. 18:23,24; 20:3), the land itself begins to “vomit” them out as the body heaves under the load of internal poisons (Lev. 18:25, 27-30). . . . [William Benton] Greene likens this action on God’s part, not to doing evil that good may come, but doing good in spite of certain evil consequences, just as a surgeon does not refrain from amputating a gangrenous limb even though in so doing he cannot help cutting off much healthy flesh.{21}

Kaiser goes on to note that when nations repent, God withholds judgment (Jer. 18:7,8). “Thus, Canaan had, as it were, a final forty-year countdown as they heard of the events in Egypt, at the crossing of the Red Sea, and what happened to the kings who opposed Israel along the way.” They knew about the Israelites (Josh. 2:10-14). “Thus God waited for the ‘cup of iniquity’ to fill up–and fill up it did without any signs of change in spite of the marvelous signs given so that the nations, along with Pharaoh and the Egyptians, ‘might know that He was the Lord.’”{22}

One more point. Stephanie seemed to think that God still does things today as He did in Old Testament times. When I told her that God does not require all the same things of us today that He required of the Israelites, she said that “the advantage of the absoluteness of the biblical morality you wish to trumpet is negated by your softening of OT law and by your making local and relative the very commandments of God.” In other words, we say there are absolutes, but we give ourselves a way out. I simply noted that where it was commanded by God, for example, to put a rebellious son to death, we do not soften that command at all. But when in God’s own economy He brings about change, we go with the new way. God doesn’t change, but His requirements for His people have changed at times. This doesn’t leave everything open, however. The question is, What has God called us to do today?

Its Harmful Effects on Us

For Stephanie, biblical instruction on morality not only reveals a God she can’t trust, it also is harmful for us, too. So, for example, she says, “The desire not to harm can be overcome by the desire to do right by [one’s] idea of God (look at Abraham, my favorite enigma). That’s where the real harm to society can creep in.” She believes that the certainty of religious dogmatism regarding it own rightness encourages “excesses,” such as “holy wars and terrorism for possession of the holy land, and the killing of doctors and homosexuals for their own good.” She said that Christianity permits the kind of horrors we accuse atheists of perpetrating but with the endorsement of God. “Hitler was a very devout Catholic, as I understand it,” she said.

There is serious confusion here. Loaded words like “terrorism” bias the issue unfairly, and Stephanie takes some “excesses” to be rooted in Scripture when in fact they have nothing to do with biblical morality. It is unfair of her and other atheists to ignore the commands of Scripture that clearly reflect God’s goodness while ignoring sound interpretive methods for understanding the harder parts. It’s also wrong to let religious fanaticism in general count against God. Just as some atheists aren’t going to live up to Stephanie’s high standards, some Christians don’t live up to God’s. Gene Edward Veith says that, while Hitler had a “perverse admiration for Catholicism,” he “hated Christianity.”{23} What is clear is that there is no biblical basis for Hitler’s atrocities. To return to the point I tried to make earlier, if he looked, Hitler could have found moral injunctions in Christianity to oppose his actions. Naturalists, on the other hand, have no such standard by which to measure anyone’s actions. Conclusion

We have attempted to respond to Stephanie’s three main objections to believing in God: there’s not enough evidence; it adds nothing to what we can know from science; and theism is bad for people. These are stock objections atheists present. I think they have good answers. The next step is to try to take the atheist to the place where she or he can “see” God. Removing the reasons for rejecting God is one step in the process. The next step is to show her God. I can think of no better way to do that than to take her to Jesus, who “is the radiance of His glory and the exact representation of His nature” (Heb. 1:3). I recommended that Stephanie read one or more of the Gospels, and she said she would read John. This is the point of apologetics, to take people to the Lord in the presence of whom they must make a choice. Now we’ll wait to see what happens.

Notes

1. Rick Wade, The Relevance of Christianity (Probe Ministries, 1998).

2. Stephanie is aware of this program, and has given me permission to use her name.

3. George Smith, Atheism: The Case Against God (Buffalo, N.Y.: Prometheus Books, 1989), 98.

4. One is reminded of the time when the eighteenth century mathematician and physicist the Marquis de Laplace was asked where God fit in his theory of celestial mechanics. He replied, “I have no need of that hypothesis.”

5. W. K. Clifford, “The Ethics of Belief,” in Readings in the Philosophy of Religion, ed. Baruch A. Brody (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1974), 246.

6. Antony Flew, “The Presumption of Atheism,” in Faith and Reason (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), 337-38. See also George Smith, Atheism: The Case Against God (Buffalo, N.Y.: Prometheus Books, 1989), 7-8.

7. Alvin Plantinga and Nicholas Wolterstorff, Faith and Rationality: Reason and Belief in God (Notre Dame: Univ. of Notre Dame Press, 1983), 28.

8. Huston Smith, Beyond the Post-Modern Mind, rev. ed. (Wheaton: Quest Books, 1989), 85.

9. Kelly James Clark, Return to Reason (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1990), 126-28. I am indebted to this book for this portion of my discussion.

10. A good introduction to the evidentialist objection and this kind of response to it (what is being called Reformed epistemology) is found in Clark, Return to Reason. See also J.P. Moreland, Scaling the Secular City; A Defense of Christianity (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1987), 116-17. The seminal work is Plantinga and Wolterstorff, Faith and Rationality.

11. Francis A. Schaeffer, The God Who is There (Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 1968), 128-130.

12. Moreland, Scaling the Secular City, 120ff.

13. William Lane Craig, Reasonable Faith: Christian Truth and Apologetics, rev. ed. (Wheaton: Crossway Books, 1994), 59.

14. Walter C. Kaiser, Jr., Toward Old Testament Ethics (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1983), 60-64.

15. Papers from the “Naturalism, Theism and the Scientific Enterprise” conference in Austin, Texas in 1997, which included several presentations on this subject can be accessed on the Web at www.dla.utexas.edu/depts/philosophy/faculty/koons/ntse/ntse.html.

16. William A. Dembski, “Science and Design,” First Things 86 (October 1998): 26-27.

17. There is an article on Probe’s web site about the problem of evil, so I’ll only make a few comments here. See Rick Rood, The Problem of Evil: How Can A Good God Allow Evil? (Probe Ministries, 1996).

18. Henri Blocher, Evil and the Cross (Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 1994), 102-03.

19. For a in-depth discussion of the moral difficulties in the Old Testament, the reader might want to refer to Kaiser, Toward Old Testament Ethics, in which he devotes three chapters to such difficulties.

20. W. H. Griffith Thomas, Genesis: A Devotional Commentary (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1946), 197.

21. Kaiser, 267-68.

22. Kaiser, 268.

23. Gene Edward Veith, Modern Fascism: Liquidating the Judeo-Christian Worldview (Saint Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 1993), 50.

©2000 Probe Ministries.

Lael Arrington has written a truly wonderful and exceptionally helpful book, Worldproofing Your Kids,

Lael Arrington has written a truly wonderful and exceptionally helpful book, Worldproofing Your Kids,

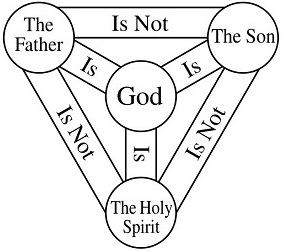

Even though it’s short, this definition is both a mouthful and a mind full. But let’s settle on four basic concepts before we move on to the implications. At the heart of the definition of the Blessed Trinity we have: one God, three Persons, who are coequal and coeternal. With this sketch in place, then, we are ready to move out and survey the importance of the Trinity with respect to the Christian worldview and its practical aspects for the Christian life. At the end of our discussion I truly hope that we can affirm together our love for the Trinity.

Even though it’s short, this definition is both a mouthful and a mind full. But let’s settle on four basic concepts before we move on to the implications. At the heart of the definition of the Blessed Trinity we have: one God, three Persons, who are coequal and coeternal. With this sketch in place, then, we are ready to move out and survey the importance of the Trinity with respect to the Christian worldview and its practical aspects for the Christian life. At the end of our discussion I truly hope that we can affirm together our love for the Trinity.