What began as a coming together to fight abortion has become a serious dialogue between evangelicals and Catholics. Rick Wade introduces the conversation.

This article is also available in Spanish.

This article is also available in Spanish.

The Cultural Crisis and the Plea of Jesus

Sometime in 1983 I began working with the Crisis Pregnancy Center in Chicago. A few times I participated in sidewalk protests in front of abortion clinics. I son realized that many of those I stood with on the sidewalks were Roman Catholics! I even had the opportunity to speak before a group of Catholics once. As I soon learned, Catholics had been fighting abortion for some time before such people as Francis Schaeffer made evangelical Protestants aware of the situation.

Roman Catholicism was a bit of a mystery to me then. There weren’t many Catholics in southeast Virginia where I grew up. All I knew was that they had a Pope and they prayed to Mary and they sometimes had little statues in their front yards. The lines were pretty clearly drawn between them and us. Now I was being forced to think about these people and their beliefs, for here we were standing side by side ministering together in the name of Jesus.

Cultural/Moral Decline

At the grassroots level, Christians of varying stripes have found themselves working to stem the tide of immorality together with those they never thought they’d be working with. In the 1980s, abortion was perhaps the most visible example of a gulf that was widening in America. Not only abortion, but illegitimacy, sexual license in its various forms, a skyrocketing divorce rate and other social ills divided those who accepted traditional, Judeo-Christian morality from those who didn’t. People began talking about the “culture war.” Because our influence has waned, we have found that we no longer have the luxury of casting stones at “those Catholics over there,” for we are being forced by our cultural circumstances to work at protecting a mutually held set of values.

In the book Evangelicals and Catholics: Toward a Common Mission, Chuck Colson reviews the social/ethical shift in America.{2} With the loss of confidence in our ability to know universal, objective truth, we have turned to the subjective and practical. Getting things done is what counts. Power has replaced reason as the primary tool for change. Liberal politics determines the readings offered in literature courses in colleges. Radical multiculturalism has skewed representations of the West to make us the source of oppression for the rest of the world. “Just as the loss of truth leads to the loss of cultural integrity,” says Colson, “so the loss of cultural integrity results in the disintegration of common moral order and its expression in political consensus.”{3} Individual choice trumps the common good; each has his or her own rules. Abortion is a choice. The practice of homosexuality is a choice. Self-expression is the essence of freedom, regardless of how it affects others. And on it goes.

One of the ironic consequences of this potentially is the loss of the freedom we so desperately seek. This is because there must be some order in society. If everyone goes in different directions, the government will have to step in to establish order. What are Christians to do? Evangelicals are strong in the area of evangelism. Is there more that can be done on the cultural level?

The Grassroots Response

Back to the sidewalks of Chicago. “In front of abortion clinics,” says Colson, “Catholics join hands with Baptists, Methodists, and Episcopalians to pray and sing hymns. Side by side they pass out pamphlets and urge incoming women to spare their babies.” This new coming together extends to other areas as well. Colson continues:

Both evangelicals and Catholics are offended by the blasphemy, violence, and sexual promiscuity endorsed by both the artistic elite and the popular culture in America today. On university campuses, evangelical students whose Christian faith comes under frequent assault often find Catholic professors to be their only allies. Evangelicals cheer as a Catholic nun, having devoted her life to serving the poor in the name of Christ, boldly confronts the president of the United States over his pro-abortion policies. Thousands of Catholic young people join the True Love Waits movement, in which teenagers pledge to save sex for marriage, a program that originated with Baptists.{4}

This has provided the groundwork for what is being called the “new ecumenism,” a recent upsurge in interest in finding common cause with others who believe in Jesus Christ as the divine Son of God. Having seen this new grassroots unity in the cause of Christian morality, scholars and pastors are meeting together to see where the different traditions of Christians agree and disagree with each other, with a view to presenting a united front in the culture war.

Jesus’ Prayer

Speaking of His church, Jesus asked the Father, “that they may all be one, just as you, Father, are in me, and I in you, that they also may be in us, so that the world may believe that you have sent me. . . . I in them and you in me, that they may become perfectly one, so that the world may know that you sent me and loved them even as you loved me.” (John 17:21-23 ESV) In addition to the culture war, Christians have as a motive for unity the prayer of Jesus. Division in the Church is like a body divided: how will it work as a unit to accomplish its tasks? Jesus was not talking about unity at any price, but we can’t let that idea prevent us from seeking it where it is legitimate in God’s eyes.

The New Ecumenism

The cultural shift and the prayer of Jesus have led thinkers in the different Christian traditions to come together to see what can be done to promote the cause of unity. A conversation which began in earnest with the participants of Evangelicals and Catholics Together in the mid-’90s has branched out resulting in magazines, books and conferences devoted to this issue. In fact, in November 2001, I attended a conference called “Christian Unity and the Divisions We Must Sustain,” which included Evangelicals, Catholics and Eastern Orthodox believers.{5}

Participants in these discussions refer to themselves as “traditional” Christians. By “traditional” they mean those who “are freely bound by a normative tradition that is the bearer of truth,” in the words of Richard John Neuhaus.{6} Traditional Christians trace their heritage back to the apostles, rather than adopting as ultimately authoritative the ideas of modern scholarship. They accept the Bible as the authoritative Word of God and the great creeds of the early centuries as summaries of authentic apostolic teaching. They agree on such things as the Trinity, the Virgin Birth, and salvation through Jesus Christ the divine Son of God. Because of their acceptance of such fundamental truths, it is often noted that a traditional Evangelical has more in common with a traditional Catholic than with a liberal Protestant who denies the deity of Christ and other fundamental Christian truths.

20th Century Ecumenical Movement

For some of our older readers the word ecumenical probably brings to mind the movement of the 20th century spearheaded by the World Council of Churches and the National Council of Churches, which took a decidedly unbiblical turn in the mid 1960s. I can remember hearing people in my church speak of it is very disparaging tones. Is this new ecumenism like the old one?

Participants take great pains to distinguish the new ecumenism from the old one. The latter began in 1910 in Edinburgh for the purpose of bringing Protestants together, primarily for missions.{7} At first its aims were admirable. After World War II, however, the focus shifted to the social and political. In 1966 at theWorld Conference on Church and Society the shift became public. “Thereafter the ideological radicals increased,” says theologian Tom Oden. The movement took a turn “toward revolutionary rhetoric, social engineering, and regulatory politics.”{8} It tried to form alliances around the “edges” of Christian life and belief, so to speak. In other words, it was interested in what the Church’s role was in the world on the social and political level. Orthodox doctrine became expendable when inconvenient. Today that movement is floundering, and some predict it won’t last much longer.

The New/Old Ecumenism

The new ecumenism, on the other hand, rejects the demands of modernity, which seeks to supplant ancient apostolic truth with its own wisdom, and instead allows apostolic truth to become modernity’s critic. Oden says that, “We cannot rightly confess the unity of the church without re-grounding that unity in the apostolic teaching that was hammered out on the anvil of martyrdom and defined by the early conciliar process, when heresies were rejected and the ancient orthodox consensus defined.”{9}

The new ecumenists look to Scripture and to the early ecumenical creeds like the Apostles Creed as definitive of Christian doctrine. With all their differences they look to a core of beliefs held historically upon which they all agree. From this basis they then discuss their differences and consider what they together might do to influence their society with the Christian worldview.

In this day of postmodern relativism and constructivism, it would be easy to see this discussion as another example of picking and choosing one’s truths; or putting together beliefs we find suited to our tastes with no regard for whether they’re really true. This isn’t the attitude being brought to this subject; the new ecumenism insists on the primacy of truth. This means that discussions can be rather intense, for the participants don’t feel the freedom to manipulate doctrine in order to reach consensus. At the “Christian Unity” conference speakers stated boldly where they believed their tradition was correct and others incorrect, and they expected the same boldness from others. There was no rancor, but neither was there any waffling. I overheard one Catholic congratulate Al Mohler, a Baptist, on his talk in which Mohler made it clear that, according to evangelical theology, Rome was simply wrong. “May your tribe increase!” the Catholic priest said. Not because he himself didn’t care about theological distinctions or was trying to work out some kind of postmodern mixing and matching of beliefs. No, it was because he appreciated the fact that Mohler was willing to stand firm on what he believes to be true. This attitude is necessary not only to maintain theological integrity within the Church but is essential if we wish to give our culture something it doesn’t already have.

This is the spirit, says Tom Oden, a Methodist theologian, of the earliest ecumenism–that of the early Church–which produced the great creeds of the faith. Oden provides a nice summary of the differences between the two ecumenisms. Whereas the old ecumenism of the 20th C. distrusted the ancient ecumenism, the new one embraces it. The old one accommodated modernism uncritically, whereas the new is critical of the failed ideas of modernism. The former was utopian, the latter realistic. The former sought negotiated unity, whereas the latter is based on truth. The former was politics-driven the latter is Spirit-led.{10}

Meetings and Documents

How did this movement shift from abortion mill sidewalks to the conference rooms of Christian scholars? In the early ’90s, Charles Colson and Richard John Neuhaus began leading a series of discussions between Evangelical and Catholic scholars which produced in 1994 a document titled “Evangelicals and Catholics Together: The Christian Mission in the Third Millennium.”{11} In the introductory section one finds this statement summarizing their fundamental conviction:

As Christ is one, so the Christian mission is one. That one mission can be and should be advanced in diverse ways. Legitimate diversity, however, should not be confused with existing divisions between Christians that obscure the one Christ and hinder the one mission. There is a necessary connection between the visible unity of Christians and the mission of the one Christ. We together pray for the fulfillment of the prayer of Our lord: “May they all be one; as you, Father, are in me, and I in you, so also may they be in us, that the world may believe that you sent me.” (John 17)

Based upon this conviction they go on to discuss agreements, disagreements, and hopes for the future. Participants in the discussion included such Evangelicals as Kent Hill, Richard Land, and John White. Such notables as J.I. Packer,{12} Nathan Hatch, Thomas Oden, Pat Robertson, Richard Mouw, and Os Guinness endorsed the document.

This document was followed in 1998 by one titled “The Gift of Salvation,” which discusses the issues of justification and baptism and others related to salvation. The level of agreement indicated drew some strong criticisms from some Evangelical scholars,{13} the main source of contention being the doctrine of justification, a central issue in the Reformation. Critics didn’t find the line as clearly drawn as they would like. Is justification purely forensic? In other words, is it simply a matter of God declaring us righteous apart from anything whatsoever we do (the Protestant view)? Or is it intrinsic, in other words, a matter of God working something in us which becomes part of our justification(the Catholic view)? To put it another way, is it purely external or internal? Or is it both?{14}

In May, 1995, the Fellowship of St. James and Rose Hill College sponsored a series of talks between evangelical Protestants, Eastern Orthodox and Roman Catholics with a view to doing much the same as Evangelicals and Catholics Together except that Orthodox Christians were involved.{15} Participants included Richard John Neuhaus, Harold O.J. Brown, Patrick Henry Reardon, Peter Kreeft, J.I. Packer, and Kallistos Ware. As James Cutsinger writes, the purpose was “to test whether an ecumenical orthodoxy, solidly based on the classic Christian faith as expressed in the Scripture and ecumenical councils, could become the foundation for a unified and transformative witness to the present age.”{16} An important theme of this conference, as with ECT, was truth. Says Neuhaus: “The new ecumenism, as reflected also in ECT, is adamant that truth and unity must not be pitted against one another, that the only unity we seek is unity in the truth, and the only truth we acknowledge is the truth by which we are united.”{17}

Two Projects

There are two projects guiding this discussion which sometimes overlap but often don’t. The first is the culture war. Some are convinced that there cannot be full communion between the traditions because our doctrinal differences are too significant, so we should stick to doing battle with our culture over the moral issues of the day. After all, this is where the conversation began. Here, it is the broader Christian worldview which is important, not so much detailed questions about justification and baptism and so on. What these scholars hope to do is make us aware of our commonalities so we feel free to minister together in certain arenas, and then to rally each other to the cause of presenting a Christian view in matters of social and cultural importance today

The second project is shaped by Jesus’ prayer that we be united. Having seen that we do believe some things in common, as evidenced by the fight against abortion, the next step is to dig more deeply and see if we can find a more fundamental unity. The focus here is on theological agreements and disagreements. The beliefs of all involved come under scrutiny. Some scholars will be satisfied with discovering and clarifying beliefs held in common. Others state boldly that the goal can be none other than full communion between traditions if not the joining of all into one.

Impulse of the Holy Spirit

Participants are convinced that this is a move of the Holy Spirit. How else could those who have battled for so long and who are so convinced of the truth of their own tradition be willing to discuss these matters with the real hope of being drawn closer together? Theologian Tom Oden says this: “What is happening? God is awakening in grass roots Christianity a ground swell of longing for classic ecumenical teaching in all communions. There are innumerable lay embodiments of this unity.”{18} There is a new longing to go back to our roots to rediscover our historical identity in the face of a world that leaves identity up for grabs. Could it be that the Spirit is indeed working to bring the church closer together in our day?

Theological Agreements and Disagreements

As noted previously, those who participate in the new ecumenism refer to themselves as “traditional Christians.” They look to the early church to rediscover their roots. They hold to the Apostles and Nicene Creeds and others of the early ecumenical creeds.

J.I. Packer provides a helpful summary of the doctrines traditional Christians hold. They are:

- The canonical Scriptures as the repository and channel of Christ-centered divine revelation.

- The triune God as sovereign in creation , providence and grace.

- Faith in Jesus Christ as God incarnate, the one mediator between God and man.

- Seeing Christians as a family of forgiven sinners . . . empowered for godliness by the Holy Spirit.

- Seeing the church as a single supernatural society.

- The sacraments of baptism and Holy Communion “as necessities of obedience, gestures of worship and means of communion with God in Christ.”

- The practice of prayer, obedience, love and service.

- Dealing appropriately with the personal reality of evil.

- Expecting death and final judgment to lead into the endless joy of heaven.”{19}

Because Roman Catholicism is such an unknown to many evangelicals, it is just assumed by many that its teachings are all radically different from our own. The list of doctrines just given, however, proves how close we are on central issues. In fact, the well-respected Presbyterian theologian J. Gresham Machen said this in the context of his battles with liberalism:

How great is the common heritage that unites the Roman Catholic Church, with it maintenance of the authority of Scripture and with it acceptance of the great early creeds, to devout Protestants today! We would not indeed obscure the difference which divides us from Rome. The gulf is indeed profound. But profound as it is, it seems almost trifling compared to the abyss which stands between us and many ministers of our own church.{20}

With all this in common, however, we must recognize our differences as well since they are significant. Roman Catholics believe the church magisterium is the ultimately authoritative voice for the church since it is the church that has been made the pillar and ground of the truth. At the very head, of course, is the Pope who is believed to be the successor of Peter. Protestants emphasize the priesthood of the believer for whom Scripture is the final authority. Catholics believe the grace of God unto salvation is mediated through baptism while Protestants see baptism more as symbolic than as efficacious. Catholics revere Mary and pray to her and the saints. Evangelicals see Mary as a woman born in sin who committed sin herself, but who was specially blessed by God.{21}

Probably the most important difference between Catholics and Protestants is over the matter of how a person is accepted before God. What does it mean to be justified? How is one justified? This was the whole issue of the Reformation for Martin Luther, according to Michael Horton.{22} If one’s answer to the question, “What must I do to be saved?” is deficient, does it matter what else one believes? The answer to this will be determined by what one’s goals are in seeking unity. Are we working on the project of ecclesial unity? Or are we concerned mostly with the culture war? Our disagreements are more significant for the former than for the latter.

What is the significance of our differences? The significance will relate to our goals for coming together. The big question in the new ecumenism is in what areas can we come together? In theology and then in cultural involvement? Or just in cultural involvement? Some are working hard to see where we agree and disagree theologically, even to the point of examining their own tradition to be certain they have it correct (at least, as they see it). Others believe that while we share many fundamental doctrinal beliefs, the divisions can’t be overcome without actually becoming one visible church. Cultural involvement–cultural cobelligerency it has been called–becomes the focus of our unity.

Some readers might have a question nagging at them about now. That is this: If Catholics have a deficient understanding of the process of salvation, as we think they do, can they even be Christians? Shouldn’t we be evangelizing them rather than working with them?

Surely there are individuals in the Catholic Church who have no reason to hope for heaven. But the same is true in Evangelical churches. Although of course we want to understand correctly and teach accurately the truth about justification, we must remember that we come to Christ through faith in Him, not on the basis of the correctness of our detailed doctrine of justification. How many new (genuine) converts in any tradition can explain justification? J.I. Packer chastises those who believe the mercy of God “rests on persons who are notionally correct.”{23} Having read some Catholic expositions of Scripture and devotional writing–even by the Pope himself–it is hard to believe I’m reading the words of the anti-Christ (something Protestants have been known to call the Pope) or that these writers aren’t Christians at all. Again, this isn’t to diminish the rightful significance of the doctrine of justification, but to seek a proper understanding of the importance of one’s understanding of the doctrine before one can be saved.

There is no doubt that there are Christians in the Roman Catholic Church as assuredly as there are non-Christians in Evangelical churches. We should be about the task of evangelism everywhere. As with everyone our testimony should be clear to Catholics around us. If they indicate that they don’t know Christ then we tell them how they can know him. What we dare not do is have the attitude, “Well, he’s Catholic so he can’t be saved.”

Options for Unity

I see three possible frameworks for unity. One is unity on the social/cultural/political level. In these areas we can bring conservative religious thinking to bear on the issues of the day. I think this is what Peter Kreeft is calling for in an article titled “Ecumenical Jihad,” in which he broadens the circle enough to include Jews and Muslims.{24}

The second option is full, ecclesial unity. The focus here is on Jesus’ prayer for unity. As Christ is one, we are to be one. This goes beyond cooperation in the public square; this is a call for one Church–one visible institution. Neuhaus says we are one church, we just aren’t acting like it. One writer points out that this kind of unity “is a ‘costly act’ involving the death and rebirth of existing confessional churches.”{25} Catholic theologian Avery Dulles believes that such full unity might be legitimate between groups that have a common heritage, such as Catholics and Eastern Orthodox. “But that goal is neither realistic nor desirable for communities as widely separated as evangelicals and Catholics. For the present and the foreseeable future the two will continue to constitute distinct religious families.”{26} The stresses such a union would create would be too much.

A third possibility is a middle way between the first two. It involves the recognition of a mutually held Christian worldview with an acknowledgement and acceptance of our differences, and with a view to peace between traditions and teamwork in the culture war. Here, theology is important; evangelicals share something with Catholics that they don’t with, say, Muslims who are morally conservative. These could stand with Abraham Kuyper, the Prime Minister of Holland in the late 19th century who said,

Now, in this conflict [against liberalism] Rome is not an antagonist, but stands on our side, inasmuch as she recognizes and maintains the Trinity, the Deity of Christ, the Cross as an atoning sacrifice, the scriptures as the Word of God, and the Ten Commandments. Therefore, let me ask if Romish theologians take up the sword to do valiant and skillful battle against the same tendency that we ourselves mean to fight to death, is it not the part of wisdom to accept the valuable help of their elucidation?{27}

Kuyper here was dealing with liberal theology. But the principle holds for the present context. If Kuyper could look to the Catholic Church for support in theological matters to some extent against liberal Protestants, surely we can join with them in speaking to and standing against a culture of practical atheism.

Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger has proposed a two-prong strategy for achieving church unity. The first task is complete, visible unity as called for in the “Decree on Ecumenism.” Full unity, however, can only come about by a special work of the Holy Spirit. “The second task . . . is to pursue intermediate goals.” He says:

It should be clear that we do not create unity, no more than we bring about righteousness by means of our works, but that on the other hand we should not sit around twiddling our thumbs. Here it would therefore be a question of continually learning afresh from the other as other while respecting his or her otherness.{28}

Avery Dulles says that the heterogeneous community of Catholics and evangelicals still has much to do together. “They can join in their fundamental witness to Christ and the gospel. They can affirm together their acceptance of the apostolic faith enshrined in the creeds and dogmas of the early Church. . . . They can jointly protest against the false and debilitating creeds of militant secularism. In all these ways they can savor and deepen the unity that is already theirs in Christ.”{29}

Dulles offers some advice on what to do in this interim period.{30} I’ll let them stand without comment:

- Seek to correct misunderstandings about the other tradition.

- Be surprised at the graciousness of God, who continues to bestow his favors even upon those whose faith comes to expression in ways that we may consider faulty.

- Respect each other’s freedom and integrity.

- Instead of following the path of reduction to some common denominator, the parties should pursue an ecumenism of mutual enrichment, asking how much they can give to, and receive from, one another.

- Rejoice at the very significant bonds of faith and practice that already unite us, notwithstanding our differences. (Reading the same Scriptures, confessing the same Triune God and Jesus as true God and true man, etc.)

- We can engage in joint witness in our social action.

- Pray for the work of the Spirit in restoring unity, and rest in knowing it has to be His work and not ours.

Protesting Voices

Not all Evangelical scholars and church leaders are in favor of the Roman Catholic/Evangelical dialogue, at least with the document “Evangelicals and Catholics Together.” Such well-known representatives as R.C. Sproul, John MacArthur, Michael Horton, and D. James Kennedy have taken issue with important parts of this document.

The basis of the ECT dialogue was the conviction that “Evangelicals and Catholics are brothers and sisters in Christ.”{31} It was upon this foundation that the two groups came together to consider a Christian response to current social issues. But some question whether such a sweeping statement is correct. Are we really “brothers and sisters in Christ”?

MacArthur presents the central concerns in an article in the journal of The Master’s Seminary, of which he is president. He believes “Evangelicals and Catholics Together” was so concerned about social issues that it downplayed and compromised key doctrines.

The fundamental issue is the matter of justification. Are we saved by faith plus works, or by faith alone? Is justification imputed or infused (Are we declared righteous or are we made righteous?)? The Council of Trent, convened by the Roman Church in the late 16th century, anathematized those who believe “that faith alone in the divine promises is sufficient for the obtaining of grace” (Trent, sess. 7, canon 8).”{32} Trent also made plain that justification is obtained through the sacrament of baptism (Trent, sess. 6, chap. 7).{33} Furthermore, the Roman Church holds that justification is an ongoing process by which we are made righteous, not a declaration that we are righteous. MacArthur contends that this constitutes a different gospel.

R.C. Sproul says this: “The question in the sixteenth century remains in dispute. Is justification by faith alone a necessary and essential element of the gospel? Must a church confess sola fide in order to be a true church? Or can a church reject or condemn justification by faith alone and still be a true church? The Reformers certainly did not think so. Apparently the framers and signers of ECT think otherwise.”{34}

MacArthur insists that, even though we might all be able to recite the Apostles’ Creed together, if we differ on the core matter of the Gospel we’re talking about different religions altogether. If Evangelicalism and Roman Catholicism are different religions, how can we claim to be “brothers and sisters in Christ”?{35}

Thus, there are some who believe the dialogue between Evangelicals and Roman Catholics to be a misbegotten venture. However, even among those who take a strong position on the Reformation view of justification, there are some who still see some value in finding common cause with Catholics on social matters. For example, a statement signed by John Armstrong, the late James Montgomery Boice, Michael Horton, and R.C. Sproul among others–who also signed “An Appeal to Fellow Evangelicals,” a strong statement against the Roman view of justification–says this: “The extent of the creedal consensus that binds orthodox Evangelicals and Roman Catholics together warrants the making of common cause on moral and cultural issues in society. Roman Catholics and Evangelicals have every reason to join minds, hearts, and hands when Christian values and behavioral patterns are at stake.” This doesn’t preclude, however, the priority of the fulfillment of the Great Commission.{36}

The Importance of the Issue

There are several reasons why the current conversations between Evangelicals and Catholics (and Eastern Orthodox as well) are important. First is simply the reaffirmation of what we believe. In this day of skepticism about the possibility of knowing what is true at all, and the practice of many of picking and choosing beliefs according to their practical functionality, it is good to think carefully through what we believe and why. A woman I know told me she doesn’t concern herself with all those denominational differences. “I just love Jesus,” she said. “Just give me Jesus.” One gets the sense from all that is taught us in Scripture that Jesus wants us to have more, meaning a more fleshed-out understanding of God and His ways. As we review our likenesses and differences with Roman Catholics we’re forced to come to a deeper understanding of our own beliefs.

We also have Jesus’ high priestly prayer in which he prays fervently for unity in his body. Was he serious? Is it good enough to simply say “Well, the Roman Church differs in its doctrine of justification so they can’t be Christians,” and turn away from them? Or to keep a distance from them because they believe differently on some things? While not giving up our own convictions, isn’t it worthwhile taking the time to be sure about our own beliefs and those of others before saying Jesus’ prayer doesn’t apply?

J.I. Packer says this: “However much historic splits may have been justified as the only way to preserve faith, wisdom and spiritual life intact at a particular time, continuing them in complacency and without unease is unwarrantable.”{37} A simple recognition of the common ground upon which we stand would be a step forward in answering Jesus’ prayer. The debates which will follow as our differences are once again made clear can further us in our theological understanding and our kingdom connectedness.

Of course, the culture war which brought about this discussion in the first place is another good reason for coming together. Discovering our similarities in moral understanding will open doors of cooperative ministry and witness in society. Chuck Colson believes that the only solution to the current cultural crisis “is a recultivation of conscience.”{38} How can the conscience be recultivated? “At root, every issue that divides the American people,” Colson says, “is religious in essence.”{39} It will take a recultivation of the knowledge of God to bring about change. Sharing the same basic worldview, we can speak together in the public square on the issues of the day.

Finally, consider what we can learn from one another. Evangelicals can profit from the deep theological and philosophical study of Catholic scholars, while Catholics can learn from Evangelicals about in-depth Bible study. Evangelicals can learn from Catholics what it is to be a community of believers since, for them, the Church has the emphasis over the individual. Catholics, on the other hand, can learn from Evangelicals what it means to have a personal walk with Christ.

In sum, there are important, legitimate discussions or debates which must be held in the Church over theological issues. But such discussions can only be held if we are talking to each other. We are obligated to our Lord to seek the unity for which He prayed. This isn’t a unity of convenience, but a unity based upon truth. If one studies the issues closely and determines that our differences are too great to permit any coming together on the ecclesial level, at least one should see the value of joining together on the cultural level–of speaking the truth about the one true God who sent his only Son to redeem mankind, and who has revealed his moral standard in nature and Scripture, a standard which will be ignored to our destruction.

Notes

1. The Evangelical/Roman Catholic dialogue is a serious matter. Although this article isn’t presented as a critique, it was thought that the lack of a protesting voice in the original article might imply this writer’s (and Probe’s) full endorsement of the dialogue, or even an implicit endorsement of ecclesial unity. A conversation that brings into question the central issue of the Reformation, justification by faith, deserves close scrutiny. Thus, a revision was made to the original article to include a few protesting voices.

2. Charles Colson, “The Common Cultural Task: The Culture War from a Protestant Perspective, ” in Charles Colson and Richard John Neuhaus, eds., Evangelicals and Catholics Together: Toward a Common Mission (Dallas, TX: Word Publishing, 1995), 7ff.

3. Ibid., 10.

4. Ibid., 2.

5. Although this movement now includes the Eastern Orthodox Church, in this article I’ll focus on Evangelical/Catholic relations.

6. Richard John Neuhaus, “A New Thing: Ecumenism at the Threshold of the Third Millennium,” in James S. Cutsinger, Reclaiming the Great Tradition: Evangelicals, Catholics and Orthodox in

Dialogue (Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 1997), 54-55.

7. Richard John Neuhaus, “That They May Be One: Prospects for Unity in the 21st Century,” a paper delivered at the conference “Christian Unity and the Divisions We Must Sustain,” Nov. 9, 2001. Tom Oden puts the starting date for the old ecumenism as 1948.

8. Tom Oden, “The New Ecumenism and Christian Witness to Society,” Pt. 1, a revision of an address delivered Oct. 1, 2001 on the 20th anniversary of the founding of The Institute on Religion and Democracy. Downloaded from www.ird-renew.org/news/NewsPrint.cfm?ID=214&c=4 on December 3, 2001.

9. Ibid.

10. Ibid.

11. “Evangelicals and Catholics Together: The Christian Mission in the Third Millennium,” First Things 43 (May 1994) 15-22.

12. Packer defended his decision to sign the document in “Why I Signed It,” Christianity Today. December 12, 1994, 34-37.

13. For example, R.C. Sproul, Getting the Gospel Right: The Tie That Binds Evangelicals Together (Grand Rapids: Baker Books, 1999).

14. For a different twist on the doctrine from an evangelical Protestant, see S. M. Hutchens, “Getting Justification Right,” Touchstone, July/August 2000, 41-46.

15. Rose Hill College is closely tied to the Orthodox tradition.

16. James S. Cutsinger, “Introduction: Finding the Center, in Cutsinger, ed. Reclaiming, 10.

17. Neuhaus, “A New Thing,” 57.

18. Oden, “The New Ecumenism.”

19. J.I. Packer, “On from Orr: Cultural Crisis, Rational Realism and Incarnational Ontology,” in Cutsinger, 156.

20. J. Gresham Machen, Christianity and Liberalism (New York: Macmillan, 1924), 52; quoted in Colson, 39-40.

21. From discussions with former Catholics I have gotten the impression that there is a difference between authoritative Catholic theology and the beliefs of lay Catholics. We cannot take up this matter here. I’ll just note that I am looking to the writings of Catholic theologians and, in particular, to the Catholic catechism for the teachings of the Church.

22. Michael S. Horton, “What Still Keeps Us Apart?” in John Armstrong, ed., Roman Catholicism: Evangelical Protestants Analyze What Divides and Unites Us (Chicago: Moody, 1994), 251.

23. Packer, “On from Orr,” 174.

24. Peter Kreeft, “Ecumenical Jihad,” Cutsinger, ed., chap. 1.

25. Avery Dulles, “The Unity for Which We Hope,” in Colson and Neuhaus, Evangelicals and Catholics, 116-17. Dulles here provides a more detailed description of this kind of unity. Dulles discusses six different kinds of unity.

26. Ibid., 143.

27. Abraham Kuyper, Calvinism and the Future (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1898), 183-84; quoted in Colson, 39.

28. Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger, Church, Ecumenism and Politics: New Essays in Ecclesiology (New York: Crossroad, 1988), 98, quoted in Dulles, “The Unity for Which We Hope,” 137-38.

29. Dulles, “Unity,” 144.

30. Ibid., 138-140. He gives ten; I’ve included seven.

31. Colson, Evangelicals and Catholics, xviii.

32. John F. MacArthur, “Evangelicals and Catholics Together,” The Master’s Seminary Journal 6/1 (Spring 1995): 30. See also R.C. Sproul, Faith Alone: The Evangelical Doctrine of Justification (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1995).

33. MacArthur, 28.

34. Sproul, Faith Alone, 30.

35. It should be noted that, because of protests such as those of MacArthur, Sproul and others, key signers of the document later issued a statement in which they affirmed their commitment to the doctrines of “substitutionary atonement and [the] imputed righteousness of Christ, leading to a full assurance of eternal salvation; . . .” and to “the Protestant understanding of salvation by faith alone.” See “Statement By Protestant Signers to ECT,” available at www.leaderu.com/ect/ect2.html. This writer also commends for your reading the statement, “Resolutions for Roman Catholic and Evangelical Dialogue,” drafted by Michael Horton and revised by J.I. Packer, and issued by the Alliance of Confessing Evangelicals in 1994, available at http://www.alliancenet.org/pub/articles/horton.ECTresolutions.html.

36. “Resolutions for Roman Catholic and Evangelical Dialogue.” See also “An Appeal to Fellow Evangelicals,” a strong statement against the Roman view of justification available at www.alliancenet.org/month/98.08.appeal.html.

37. In another vein, Donald Bloesch believes that R.C. Sproul, in his criticism of ECT, has not “kept abreast of the noteworthy attempts in the ongoing ecumenical discussion to bridge the chasm between Trent and evangelical Protestantism.” He believes that “Sola fide still constitutes a formidable barrier in Catholic-Protestant relations, but contra Sproul, it must not be deemed insurmountable.” See his comments in “Betraying the Reformation? An Evangelical Response,” in Christianity Today, Oct. 7, 1996.

38. Packer, “On from Orr,” 157.

39. Colson, “The Common Cultural Task,” 13.

40. Ibid., 14.

©2002 Probe Ministries.

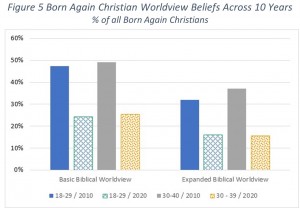

Now let’s compare these 2020 results with the results from our 2010 survey. Figure 5 shows the results across this decade for Born Again Christians looking at the percent who agree with the worldview answers above. As shown, there has been a dramatic drop in both the Basic Biblical Worldview and the Expanded Biblical Worldview.

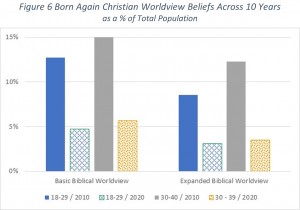

Now let’s compare these 2020 results with the results from our 2010 survey. Figure 5 shows the results across this decade for Born Again Christians looking at the percent who agree with the worldview answers above. As shown, there has been a dramatic drop in both the Basic Biblical Worldview and the Expanded Biblical Worldview. However, because the percent of the population who profess to being born again has dropped over the last ten years as well, the situation is even worse. We need to look at the percent of Americans of a particular age range who hold to a Biblical Worldview. Those results are shown in Figure 6. Once again, comparing the 18–29 age group from 2010 with the same age group ten years later now 30–39, we find an even greater drop off. For the Basic Biblical Worldview, we see a drop off from 13% of the population down to 6%. For the Expanded Biblical Worldview, the decline is from 9% down to just over 3% (a drop off of two thirds).

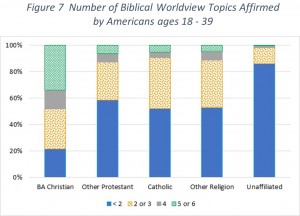

However, because the percent of the population who profess to being born again has dropped over the last ten years as well, the situation is even worse. We need to look at the percent of Americans of a particular age range who hold to a Biblical Worldview. Those results are shown in Figure 6. Once again, comparing the 18–29 age group from 2010 with the same age group ten years later now 30–39, we find an even greater drop off. For the Basic Biblical Worldview, we see a drop off from 13% of the population down to 6%. For the Expanded Biblical Worldview, the decline is from 9% down to just over 3% (a drop off of two thirds). Rather than look at the two biblical worldview levels discussed above, we will look at how many of the six biblical worldview questions they answered were consistent with a biblical worldview. In the chart, we look at 18- to 39-year-old individuals grouped by religious affiliation and map what portion answered less than two of the questions biblically, two or three, four, or more than four (i.e., five or six).

Rather than look at the two biblical worldview levels discussed above, we will look at how many of the six biblical worldview questions they answered were consistent with a biblical worldview. In the chart, we look at 18- to 39-year-old individuals grouped by religious affiliation and map what portion answered less than two of the questions biblically, two or three, four, or more than four (i.e., five or six).